Posts Tagged ‘Bacteria’

What Makes San Francisco Sourdough Unique?

Thursday, April 20th, 2017

If bagels are a New York thing, San Francisco definitely has sourdough. And probably no one has convinced more people that our sourdough is unique than Boudin Bakery, where tourists line up at Fishermanâs Wharf for a taste of that moist-tangy, fogbound delight.

Bay Area native (and KQED staffer) Peter Cavagnaro has been eating local sourdough all his life. Itâs his favorite bread. And that got him wondering about something. He asked KQED’s Bay CuriousâŠ.

âWhat makes San Francisco sourdough so unique?â

Here at KQED, weâve always heard thereâs something in the water or the air that makes our sourdough special. But is that really true?

It turns out that this is as much a science question as it is about the history and local mythology of our âauthenticâ local sourdough. By the time I had the answer, I also had 2 pounds of smelly homemade sourdough starter fermenting at home, and the results of a lab test that described the microbes living in it.

Taste the Microbes

To understand what makes our bread taste the way it does, you need to know how bread gets started. My investigation began in the fermentation room at Semifreddiâs bakery in Alameda, one of the best-known local producers of sourdough, along with Acme Bread Company and Tartine Bakery.

The fermentation room is the inner sanctum of the bakery. Itâs a very cold, stainless-steel vault where 300 yellow buckets brim with slow-bubbling beige goop: future sourdough. I stood there, shivering in a hairnet, with co-owner Mike Rose and head baker John Tredgold.

Rose is a soft-spoken man who talks about sourdough with wonderment, as if itâs alive â which it is, with millions of microbes.

âCan you hear it? Itâs hungry,â Rose said. âIt will be fed later today. It gets fed once a day. Equal parts flour and water.â

Before sourdough gets baked, it has to be grown. Born as a primordial glop, aptly called starter. All it needs to grow, as Rose said, is flour and water. And time. Thatâs it. If you add anything else, itâs not real sourdough. Eventually, the sugars in the flour start to break down, and fermentation happens on its own.

Tredgold handed me a plastic spoon and pointed me to a bucket. I could see bubbles rising to the surface of the bucket â a sure sign of microbial activity. The starter tasted like very sour yogurt to me, but Tredgold treated the experience like tasting a fine wine, smelling and savoring.

âThis is more like creme fraiche,â he said. âIt makes you salivate, it makes you excited to eat more.â

The author’s starter, looking healthy with lots of air pockets.

Flour, Water, Temperature, Time

Semifreddiâs produces 9,500 loaves of sourdough each day. But no two loaves taste exactly alike. And thatâs because the starter is alive with millions of wild yeast cells and naturally occurring bacteria. The yeast makes the bread rise. And the bacteria create the acids that make the bread sour.

The flavors vary from day to day, and batch to batch. Sourdough is one of the most ancient breads, dating back at least 5,000 years. Itâs reasonably easy to create a starter from scratch, but tricky to master the triple arts of crust, crumb and flavor when baking. So much depends on capturing enough wild yeast to make the bread light and airy. (Adding commercial yeast is not a permitted technique at the baking stage if the goal is authentic, old-fashioned sourdough).

âWe try to control it by temperature and time. And our hands. Itâs never fully totally under control, because weâre dealing with natural organisms,â said Rose. âI love it,â he added with a grin.

Rose was so passionate that I decided to try growing my own sourdough starter at home (more on that below).

The Boudin Lore

A little voice nagged at me, though. Anyone can make sourdough, but would it be authentic if it wasnât born in San Francisco? (I live in Oakland).

No one has convinced more people about the unique qualities of San Francisco sourdough than Boudin, which says itâs been selling the same loaf of bread for 168 years. According to the Boudin Bakery museum at Fishermanâs Wharf, the companyâs mother dough follows an unbroken line back to the Gold Rush in 1849. Louise Boudin even saved the starter from a burning building in the 1906 earthquake.

A museum docent told me the starter is so special and irreplaceable that the Boudin mothership sends its retail stores fresh starter every 23 days. Without it, they say the sourdough those stores produce would stop tasting like San Francisco sourdough and start tasting like San Diego or Sacramento sourdough.

Why? Well, according to the museum, Boudin bread owes its special flavor to a strain of bacteria that thrives only in San Franciscoâs climate. Scientists identified it here in 1970, so they named it Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis.

Â

Not That Unique, Actually

Itâs a great story. Too bad itâs not quite true.

Scientists did identify Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis here. But recent studies have found it in up to 90 percent of countries where sourdough is produced. So from a biological standpoint, San Francisco sourdough is not all that distinctive.

âItâs something that everyone thinks is unique to San Francisco and that is not true at all,â said Ben Wolfe, a microbiologist at Tufts University in Boston. His lab studies fermentation full time ⊠including the microbes you find in sourdough.

So, case closed? Not quite.

Boudin Bakery says their decades-old starter is the key to the bread’s flavor.

Science is still learning about the lactic acid bacteria (like L. sanfranciscensis) that give sourdough its main sour flavor. Other fermented foods have lactic acids, too, like miso, yogurt and kimchi.

But scientists donât know where they come from. Or how they get into your sourdough starter when you make it in your kitchen.

One explanation is that the bacteria could be in the flour to begin with. So when you go to the store and buy a bag of flour, itâs not sterile. They could also be on your skin or floating around your kitchen, but Wolfe says those are less likely to become the dominant bacteria in your starter.

âThis is one of the big questions weâre trying to answer in our story of American sourdough: Where are the lactic acid bacteria coming from?â said Wolfe.

The Sourdough Project

Thereâs never been a large-scale study in home kitchens to really identify the sources of bacteria at home.

Until now.

Wolfeâs lab has partnered with the Rob Dunn Lab at North Carolina State University on the Sourdough Project, the first comprehensive effort to test the DNA of sourdough starters across America â and understand the evolutionary biology that underlies the differences among starters.

The Sourdough Project is soliciting hundreds of sourdough starter samples from amateur and professional bread bakers across the country. (To participate in this public science project, get started by filling out this questionnaire).

Scientists will analyze samples to answer the baseline question: How variable are the microbes from region to region? And how much variability can be attributed to the grain of the bread, versus the air, the water or the humans involved?

There are so many factors. Wolfe ticks them off.

âIt could be the time that people ferment their breads. It could be the temperature. It could be a special set of recipes used in San Francisco than in other places.â

When I told him I was growing my own sourdough starter, he offered to analyze it.

So while science may yet discover something special is lurking in our sourdough, Wolfe isnât holding his breath.

Not even the bakers at Semifreddiâs, a company that has been in a position to benefit from the reputation of local sourdough, embrace the cachet.

Semifreddiâs head baker Tredgold says itâs pure marketing.

âIt sells the city. Itâs one of the things the cityâs known for. The bridge, the bay, the sourdough.â

And Rose, the co-owner of the bakery, added: âIf we take our local starter and bake with it in Los Angeles, I think it will taste very similar to what weâre making here,â he said.

Blasphemy! But possibly ⊠true.

My Kitchen Sourdough Experiment: Results

My own sourdough experiment lasted more than a month. I used King Arthur whole wheat flour and kept my mixture on the kitchen counter. As it grew, it smelled distressingly like vomit before it mellowed. At one point it almost spilled out of the Tupperware Iâd been keeping it in.

As my starter matured, it needed to be fed twice a day on a regular schedule. I raced home from work to give it more flour and water, spoke to it, and pampered it with field trips out to the balcony to give it some exposure to the Oakland atmosphere. (In spite of what I learned about the uncertainty of the science of microbes in sourdough, I still pictured my starter capturing beneficial wild yeast and bacteria from the atmosphere.)

I donât have pets or children, so I took photos of my starterâs regular maturity and forced my friends to admire them.

But the most important question was: How did it taste? I baked two little loaves and brought them into the KQED newsroom to get some brutally honest feedback from fellow reporters.

Julia Scott, left, and Bay Curious podcast host Olivia Allen-Price enjoy the fruits of Scott’s labor in the KQED newsroom — some homemade sourdough bread.

Being a first-time baker, you can imagine how this went. The loaves were so dense they had almost no air pockets. They weighed at least 3 pounds and were nearly rock-hard. My colleagues at KQED charitably praised the taste, but it was clear something had gone wrong in the baking process ⊠or with the starter itself.

A few weeks later, I got my sourdough DNA results back from Ben Wolfeâs Tufts lab. My starter had two bacterial species: Lactobacillus brevis and Lactobacillus plantarum; and one yeast species: Wickerhamomyces anomalus. All of which are very commonly found in sourdough starters made around the world, according to Wolfe. Itâs also common to have no more than a few species of yeast and bacteria in any given starter.

But that one bacterium once believed to make our bread so special â Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis? My bread didnât have any. Would things have gone differently if it had shown up? I may never know.

Tags: Bacteria, Bay Curious, Boudin Bakery, Food, Julia Scott, KQED, lactobacillus sanfranciscensis, microbiome, Semifreddiâs, sourdough

Posted in Podcast and Radio Work | No Comments »

A Wash On the Wild Side: How I Learned To Stop Worrying and Love My Microbiome

Sunday, May 25th, 2014

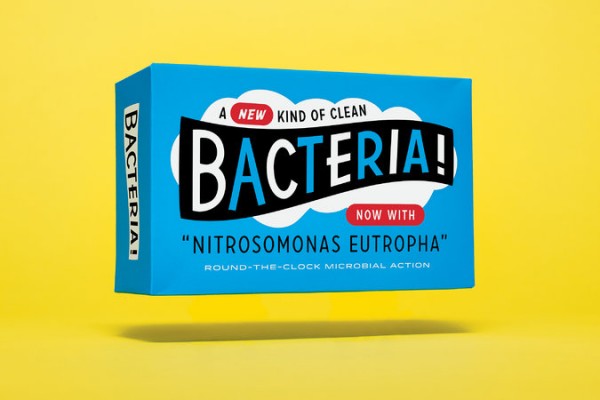

For most of my life, if Iâve thought at all about the bacteria living on my skin, it has been while trying to scrub them away. But recently I spent four weeks rubbing them in. I was Subject 26 in testing a living bacterial skin tonic, developed by AOBiome, a biotech start-up in Cambridge, Mass. The tonic looks, feels and tastes like water, but each spray bottle of AO+ Refreshing Cosmetic Mist contains billions of cultivated Nitrosomonas eutropha, an ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) that is most commonly found in dirt and untreated water. AOBiome scientists hypothesize that it once lived happily on us too â before we started washing it away with soap and shampoo â acting as a built-in cleanser, deodorant, anti-inflammatory and immune booster by feeding on the ammonia in our sweat and converting it into nitrite and nitric oxide.

In the conference room of the cramped offices that the four-person AOBiome team rents at a start-up incubator, Spiros Jamas, the chief executive, handed me a chilled bottle of the solution from the refrigerator. âThese are AOB,â he said. âTheyâre very innocuous.â Because the N. eutropha are alive, he said, they would need to be kept cold to remain stable. I would be required to mist my face, scalp and body with bacteria twice a day. I would be swabbed every week at a lab, and the samples would be analyzed to detect changes in my invisible microbial community.

In the last few years, the microbiome (sometimes referred to as âthe second genomeâ) has become a focus for the health conscious and for scientists alike. Studies like the Human Microbiome Project, a national enterprise to sequence bacterial DNA taken from 242 healthy Americans, have tagged 19 of our phyla (groupings of bacteria), each with thousands of distinct species. As Michael Pollan wrote in this magazine last year: âAs a civilization, weâve just spent the better part of a century doing our unwitting best to wreck the human-associated microbiota. . . . Whether any cures emerge from the exploration of the second genome, the implications of what has already been learned â for our sense of self, for our definition of health and for our attitude toward bacteria in general â are difficult to overstate.â

While most microbiome studies have focused on the health implications of whatâs found deep in the gut, companies like AOBiome are interested in how we can manipulate the hidden universe of organisms (bacteria, viruses and fungi) teeming throughout our glands, hair follicles and epidermis. They see long-term medical possibilities in the idea of adding skin bacteria instead of vanquishing them with antibacterials â the potential to change how we diagnose and treat serious skin ailments. But drug treatments require the approval of the Food and Drug Administration, an onerous and expensive process that can take upward of a decade. Instead, AOBiomeâs founders introduced AO+ under the loosely regulated âcosmeticsâ umbrella as a way to release their skin tonic quickly. With luck, the sales revenue will help to finance their research into drug applications. âThe cosmetic route is the quickest,â Jamas said. âThe other route is the hardest, the most expensive and the most rewarding.â

AOBiome does not market its product as an alternative to conventional cleansers, but it notes that some regular users may find themselves less reliant on soaps, moisturizers and deodorants after as little as a month. Jamas, a quiet, serial entrepreneur with a doctorate in biotechnology, incorporated N. eutropha into his hygiene routine years ago; today he uses soap just twice a week. The chairman of the companyâs board of directors, Jamie Heywood, lathers up once or twice a month and shampoos just three times a year. The most extreme case is David Whitlock, the M.I.T.-trained chemical engineer who invented AO+. He has not showered for the past 12 years. He occasionally takes a sponge bath to wash away grime but trusts his skinâs bacterial colony to do the rest. I met these men. I got close enough to shake their hands, engage in casual conversation and note that they in no way conveyed a sense of being âuncleanâ in either the visual or olfactory sense.

For my part in the AO+ study, I wanted to see what the bacteria could do quickly, and I wanted to cut down on variables, so I decided to sacrifice my own soaps, shampoo and deodorant while participating. I was determined to grow a garden of my own.

Week One

The story of AOBiome begins in 2001, in a patch of dirt on the floor of a Boston-area horse stable, where Whitlock was collecting soil samples. A few months before, an equestrienne he was dating asked him to answer a question she had long been curious about: Why did her horse like to roll in the dirt? Whitlock didnât know, but he saw an opportunity to impress.

Whitlock thought about how much horses sweat in the summer. He wondered whether the animals managed their sweat by engaging in dirt bathing. Could there be a kind of âgoodâ bacteria in the dirt that fed off perspiration? He knew there was a class of bacteria that derive their energy from ammonia rather than from carbon and grew convinced that horses (and possibly other mammals that engage in dirt bathing) would be covered in them. âThe only way that horses could evolve this behavior was if they had substantial evolutionary benefits from it,â he told me.

Whitlock gathered his samples and brought them back to his makeshift home laboratory, where he skimmed off the dirt and grew the bacteria in an ammonia solution (to simulate sweat). The strain that emerged as the hardiest was indeed an ammonia oxidizer: N. eutropha. Here was one way to test his âclean dirtâ theory: Whitlock put the bacteria in water and dumped them onto his head and body.

Some skin bacteria species double every 20 minutes; ammonia-oxidizing bacteria are much slower, doubling only every 10 hours. They are delicate creatures, so Whitlock decided to avoid showering to simulate a pre-soap living condition. âI wasnât sure what would happen,â he said, âbut I knew it would be good.â

The bacteria thrived on Whitlock. AO+ was created using bacterial cultures from his skin.

And now the bacteria were on my skin.

I had warned my friends and co-workers about my experiment, and while there were plenty of jokes â someone left a stick of deodorant on my desk; people started referring to me as âTeen Spiritâ â when I pressed them to sniff me after a few soap-free days, no one could detect a difference. Aside from my increasingly greasy hair, the real changes were invisible. By the end of the week, Jamas was happy to see test results that showed the N. eutropha had begun to settle in, finding a friendly niche within my biome.

Week Two

AOBiome is not the first company to try to leverage emerging discoveries about the skin microbiome into topical products. The skin-care aisle at my drugstore had a moisturizer with a âprobiotic complex,â which contains an extract of Lactobacillus, species unknown. Online, companies offer face masks, creams and cleansers, capitalizing on the booming market in probiotic yogurts and nutritional supplements. There is even a âfrozen yogurtâ body cleanser whose second ingredient is sodium lauryl sulfate, a potent detergent, so you can remove your healthy bacteria just as fast as you can grow them.

Audrey Gueniche, a project director in LâOrĂ©alâs research and innovation division, said the recent skin microbiome craze âhas revolutionized the way we study the skin and the results we look for.â LâOrĂ©al has patented several bacterial treatments for dry and sensitive skin, including Bifidobacterium longum extract, which it uses in a LancĂŽme product. Clinique sells a foundation with Lactobacillus ferment, and its parent company, EstĂ©e Lauder, holds a patent for skin application of Lactobacillus plantarum. But itâs unclear whether the probiotics in any of these products would actually have any effect on skin: Although a few studies have shown that Lactobacillus may reduce symptoms of eczema when taken orally, it does not live on the skin with any abundance, making it âa curious place to start for a skin probiotic,â said Michael Fischbach, a microbiologist at the University of California, San Francisco. Extracts are not alive, so they wonât be colonizing anything.

To differentiate their product from others on the market, the makers of AO+ use the term âprobioticsâ sparingly, preferring instead to refer to âmicrobiomics.â No matter what their marketing approach, at this stage the company is still in the process of defining itself. It doesnât help that the F.D.A. has no regulatory definition for âprobioticâ and has never approved such a product for therapeutic use. âThe skin microbiome is the wild frontier,â Fischbach told me. âWe know very little about what goes wrong when things go wrong and whether fixing the bacterial community is going to fix any real problems.â

I didnât really grasp how much was yet unknown until I received my skin swab results from Week 2. My overall bacterial landscape was consistent with the majority of Americansâ: Most of my bacteria fell into the genera Propionibacterium, Corynebacterium and Staphylococcus, which are among the most common groups. (S. epidermidis is one of several Staphylococcus species that reside on the skin without harming it.) But my test results also showed hundreds of unknown bacterial strains that simply havenât been classified yet.

Meanwhile, I began to regret my decision to use AO+ as a replacement for soap and shampoo. People began asking if Iâd âdone something newâ with my hair, which turned a full shade darker for being coated in oil that my scalp wouldnât stop producing. I slept with a towel over my pillow and found myself avoiding parties and public events. Mortified by my body odor, I kept my arms pinned to my sides, unless someone volunteered to smell my armpit. One friend detected the smell of onions. Another caught a whiff of âpleasant pot.â

When I visited the gym, I followed AOBiomeâs instructions, misting myself before leaving the house and again when I came home. The results: After letting the spray dry on my skin, I smelled better. Not odorless, but not as bad as I would have ordinarily. And, oddly, my feet didnât smell at all.

Week Three

My skin began to change for the better. It actually became softer and smoother, rather than dry and flaky, as though a saunaâs worth of humidity had penetrated my winter-hardened shell. And my complexion, prone to hormone-related breakouts, was clear. For the first time ever, my pores seemed to shrink. As I took my morning âshowerâ â a three-minute rinse in a bathroom devoid of hygiene products â I remembered all the antibiotics I took as a teenager to quell my acne. How funny it would be if adding bacteria were the answer all along.

Dr. Elizabeth Grice, an assistant professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania who studies the role of microbiota in wound healing and inflammatory skin disease, said she believed that discoveries about the second genome might one day not only revolutionize treatments for acne but also â as AOBiome and its biotech peers hope â help us diagnose and cure disease, heal severe lesions and more. Those with wounds that fail to respond to antibiotics could receive a probiotic cocktail adapted to fight the specific strain of infecting bacteria. Body odor could be altered to repel insects and thereby fight malaria and dengue fever. And eczema and other chronic inflammatory disorders could be ameliorated.

According to Julie Segre, a senior investigator at the National Human Genome Research Institute and a specialist on the skin microbiome, there is a strong correlation between eczema flare-ups and the colonization of Staphylococcus aureus on the skin. Segre told me that scientists donât know what triggers the bacterial bloom. But if an eczema patient could monitor their microbes in real time, they could lessen flare-ups. âJust like someone who has diabetes is checking their blood-sugar levels, a kid who had eczema would be checking their microbial-diversity levels by swabbing their skin,â Segre said.

AOBiome says its early research seems to hold promise. In-house lab results show that AOB activates enough acidified nitrite to diminish the dangerous methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). A regime of concentrated AO+ caused a hundredfold decrease of Propionibacterium acnes, often blamed for acne breakouts. And the company says that diabetic mice with skin wounds heal more quickly after two weeks of treatment with a formulation of AOB.

Soon, AOBiome will file an Investigational New Drug Application with the F.D.A. to request permission to test more concentrated forms of AOB for the treatment of diabetic ulcers and other dermatologic conditions. âItâs very, very easy to make a quack therapy; to put together a bunch of biological links to convince someone that somethingâs true,â Heywood said. âWhat would hurt us is trying to sell anything ahead of the data.â

Week Four

As my experiment drew to a close, I found myself reluctant to return to my old routine of daily shampooing and face treatments. A month earlier, I packed all my hygiene products into a cooler and hid it away. On the last day of the experiment, I opened it up, wrinkling my nose at the chemical odor. Almost everything in the cooler was a synthesized liquid surfactant, with lab-manufactured ingredients engineered to smell good and add moisture to replace the oils they washed away. I asked AOBiome which of my products was the biggest threat to the âgoodâ bacteria on my skin. The answer was equivocal: Sodium lauryl sulfate, the first ingredient in many shampoos, may be the deadliest to N. eutropha, but nearly all common liquid cleansers remove at least some of the bacteria. Antibacterial soaps are most likely the worst culprits, but even soaps made with only vegetable oils or animal fats strip the skin of AOB.

Bar soaps donât need bacteria-killing preservatives the way liquid soaps do, but they are more concentrated and more alkaline, whereas liquid soaps are often milder and closer to the natural pH of skin. Which is better for our bacteria? âThe short answer is, we donât know,â said Dr. Larry Weiss, founder of CleanWell, a botanical-cleanser manufacturer. Weiss is helping AOBiome put together a list of âbacteria-safeâ cleansers based on lab testing. In the end, I tipped most of my products into the trash and purchased a basic soap and a fragrance-free shampoo with a short list of easily pronounceable ingredients. Then I enjoyed a very long shower, hoping my robust biofilm would hang on tight.

One week after the end of the experiment, though, a final skin swab found almost no evidence of N. eutropha anywhere on my skin. It had taken me a month to coax a new colony of bacteria onto my body. It took me three showers to extirpate it. Billions of bacteria, and they had disappeared as invisibly as they arrived. I had come to think of them as âmine,â and yet I had evicted them.

– – –

BONUS: Eavesdrop on Julia’s conversation with The 6th Floor blog at the New York Times.

Tags: AOBiome, Bacteria, Bacteria skin spray, Julia Scott, Julie Segre, Lactobacillus, Michael Fischbach, New York Times Magazine, Nitrosomonas Eutropha, No poo, Probiotic cleanser, Probiotic cosmetics, Probiotic FDA regulation, Probiotics, Skin microbiome, Sodium laurel sulfate

Posted in Feature | No Comments »

© 2024 Julia Scott.