Archive for the ‘Front Page’ Category

A Wash On the Wild Side: How I Learned To Stop Worrying and Love My Microbiome

Sunday, May 25th, 2025

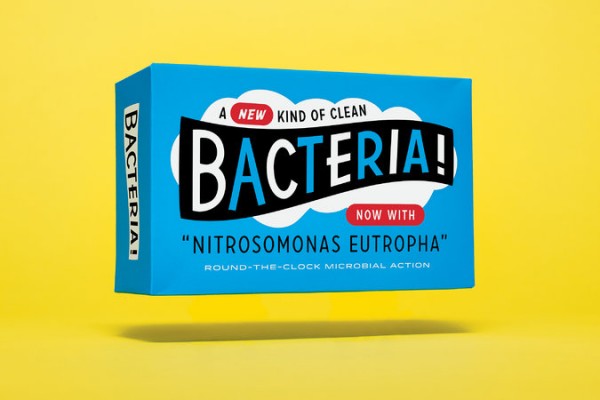

For most of my life, if Iâve thought at all about the bacteria living on my skin, it has been while trying to scrub them away. But recently I spent four weeks rubbing them in. I was Subject 26 in testing a living bacterial skin tonic, developed by AOBiome, a biotech start-up in Cambridge, Mass. The tonic looks, feels and tastes like water, but each spray bottle of AO+ Refreshing Cosmetic Mist contains billions of cultivated Nitrosomonas eutropha, an ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) that is most commonly found in dirt and untreated water. AOBiome scientists hypothesize that it once lived happily on us too â before we started washing it away with soap and shampoo â acting as a built-in cleanser, deodorant, anti-inflammatory and immune booster by feeding on the ammonia in our sweat and converting it into nitrite and nitric oxide.

In the conference room of the cramped offices that the four-person AOBiome team rents at a start-up incubator, Spiros Jamas, the chief executive, handed me a chilled bottle of the solution from the refrigerator. âThese are AOB,â he said. âTheyâre very innocuous.â Because the N. eutropha are alive, he said, they would need to be kept cold to remain stable. I would be required to mist my face, scalp and body with bacteria twice a day. I would be swabbed every week at a lab, and the samples would be analyzed to detect changes in my invisible microbial community.

In the last few years, the microbiome (sometimes referred to as âthe second genomeâ) has become a focus for the health conscious and for scientists alike. Studies like the Human Microbiome Project, a national enterprise to sequence bacterial DNA taken from 242 healthy Americans, have tagged 19 of our phyla (groupings of bacteria), each with thousands of distinct species. As Michael Pollan wrote in this magazine last year: âAs a civilization, weâve just spent the better part of a century doing our unwitting best to wreck the human-associated microbiota. . . . Whether any cures emerge from the exploration of the second genome, the implications of what has already been learned â for our sense of self, for our definition of health and for our attitude toward bacteria in general â are difficult to overstate.â

While most microbiome studies have focused on the health implications of whatâs found deep in the gut, companies like AOBiome are interested in how we can manipulate the hidden universe of organisms (bacteria, viruses and fungi) teeming throughout our glands, hair follicles and epidermis. They see long-term medical possibilities in the idea of adding skin bacteria instead of vanquishing them with antibacterials â the potential to change how we diagnose and treat serious skin ailments. But drug treatments require the approval of the Food and Drug Administration, an onerous and expensive process that can take upward of a decade. Instead, AOBiomeâs founders introduced AO+ under the loosely regulated âcosmeticsâ umbrella as a way to release their skin tonic quickly. With luck, the sales revenue will help to finance their research into drug applications. âThe cosmetic route is the quickest,â Jamas said. âThe other route is the hardest, the most expensive and the most rewarding.â

AOBiome does not market its product as an alternative to conventional cleansers, but it notes that some regular users may find themselves less reliant on soaps, moisturizers and deodorants after as little as a month. Jamas, a quiet, serial entrepreneur with a doctorate in biotechnology, incorporated N. eutropha into his hygiene routine years ago; today he uses soap just twice a week. The chairman of the companyâs board of directors, Jamie Heywood, lathers up once or twice a month and shampoos just three times a year. The most extreme case is David Whitlock, the M.I.T.-trained chemical engineer who invented AO+. He has not showered for the past 12 years. He occasionally takes a sponge bath to wash away grime but trusts his skinâs bacterial colony to do the rest. I met these men. I got close enough to shake their hands, engage in casual conversation and note that they in no way conveyed a sense of being âuncleanâ in either the visual or olfactory sense.

For my part in the AO+ study, I wanted to see what the bacteria could do quickly, and I wanted to cut down on variables, so I decided to sacrifice my own soaps, shampoo and deodorant while participating. I was determined to grow a garden of my own.

Week One

The story of AOBiome begins in 2001, in a patch of dirt on the floor of a Boston-area horse stable, where Whitlock was collecting soil samples. A few months before, an equestrienne he was dating asked him to answer a question she had long been curious about: Why did her horse like to roll in the dirt? Whitlock didnât know, but he saw an opportunity to impress.

Whitlock thought about how much horses sweat in the summer. He wondered whether the animals managed their sweat by engaging in dirt bathing. Could there be a kind of âgoodâ bacteria in the dirt that fed off perspiration? He knew there was a class of bacteria that derive their energy from ammonia rather than from carbon and grew convinced that horses (and possibly other mammals that engage in dirt bathing) would be covered in them. âThe only way that horses could evolve this behavior was if they had substantial evolutionary benefits from it,â he told me.

Whitlock gathered his samples and brought them back to his makeshift home laboratory, where he skimmed off the dirt and grew the bacteria in an ammonia solution (to simulate sweat). The strain that emerged as the hardiest was indeed an ammonia oxidizer: N. eutropha. Here was one way to test his âclean dirtâ theory: Whitlock put the bacteria in water and dumped them onto his head and body.

Some skin bacteria species double every 20 minutes; ammonia-oxidizing bacteria are much slower, doubling only every 10 hours. They are delicate creatures, so Whitlock decided to avoid showering to simulate a pre-soap living condition. âI wasnât sure what would happen,â he said, âbut I knew it would be good.â

The bacteria thrived on Whitlock. AO+ was created using bacterial cultures from his skin.

And now the bacteria were on my skin.

I had warned my friends and co-workers about my experiment, and while there were plenty of jokes â someone left a stick of deodorant on my desk; people started referring to me as âTeen Spiritâ â when I pressed them to sniff me after a few soap-free days, no one could detect a difference. Aside from my increasingly greasy hair, the real changes were invisible. By the end of the week, Jamas was happy to see test results that showed the N. eutropha had begun to settle in, finding a friendly niche within my biome.

Week Two

AOBiome is not the first company to try to leverage emerging discoveries about the skin microbiome into topical products. The skin-care aisle at my drugstore had a moisturizer with a âprobiotic complex,â which contains an extract of Lactobacillus, species unknown. Online, companies offer face masks, creams and cleansers, capitalizing on the booming market in probiotic yogurts and nutritional supplements. There is even a âfrozen yogurtâ body cleanser whose second ingredient is sodium lauryl sulfate, a potent detergent, so you can remove your healthy bacteria just as fast as you can grow them.

Audrey Gueniche, a project director in LâOrĂ©alâs research and innovation division, said the recent skin microbiome craze âhas revolutionized the way we study the skin and the results we look for.â LâOrĂ©al has patented several bacterial treatments for dry and sensitive skin, including Bifidobacterium longum extract, which it uses in a LancĂŽme product. Clinique sells a foundation with Lactobacillus ferment, and its parent company, EstĂ©e Lauder, holds a patent for skin application of Lactobacillus plantarum. But itâs unclear whether the probiotics in any of these products would actually have any effect on skin: Although a few studies have shown that Lactobacillus may reduce symptoms of eczema when taken orally, it does not live on the skin with any abundance, making it âa curious place to start for a skin probiotic,â said Michael Fischbach, a microbiologist at the University of California, San Francisco. Extracts are not alive, so they wonât be colonizing anything.

To differentiate their product from others on the market, the makers of AO+ use the term âprobioticsâ sparingly, preferring instead to refer to âmicrobiomics.â No matter what their marketing approach, at this stage the company is still in the process of defining itself. It doesnât help that the F.D.A. has no regulatory definition for âprobioticâ and has never approved such a product for therapeutic use. âThe skin microbiome is the wild frontier,â Fischbach told me. âWe know very little about what goes wrong when things go wrong and whether fixing the bacterial community is going to fix any real problems.â

I didnât really grasp how much was yet unknown until I received my skin swab results from Week 2. My overall bacterial landscape was consistent with the majority of Americansâ: Most of my bacteria fell into the genera Propionibacterium, Corynebacterium and Staphylococcus, which are among the most common groups. (S. epidermidis is one of several Staphylococcus species that reside on the skin without harming it.) But my test results also showed hundreds of unknown bacterial strains that simply havenât been classified yet.

Meanwhile, I began to regret my decision to use AO+ as a replacement for soap and shampoo. People began asking if Iâd âdone something newâ with my hair, which turned a full shade darker for being coated in oil that my scalp wouldnât stop producing. I slept with a towel over my pillow and found myself avoiding parties and public events. Mortified by my body odor, I kept my arms pinned to my sides, unless someone volunteered to smell my armpit. One friend detected the smell of onions. Another caught a whiff of âpleasant pot.â

When I visited the gym, I followed AOBiomeâs instructions, misting myself before leaving the house and again when I came home. The results: After letting the spray dry on my skin, I smelled better. Not odorless, but not as bad as I would have ordinarily. And, oddly, my feet didnât smell at all.

Week Three

My skin began to change for the better. It actually became softer and smoother, rather than dry and flaky, as though a saunaâs worth of humidity had penetrated my winter-hardened shell. And my complexion, prone to hormone-related breakouts, was clear. For the first time ever, my pores seemed to shrink. As I took my morning âshowerâ â a three-minute rinse in a bathroom devoid of hygiene products â I remembered all the antibiotics I took as a teenager to quell my acne. How funny it would be if adding bacteria were the answer all along.

Dr. Elizabeth Grice, an assistant professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania who studies the role of microbiota in wound healing and inflammatory skin disease, said she believed that discoveries about the second genome might one day not only revolutionize treatments for acne but also â as AOBiome and its biotech peers hope â help us diagnose and cure disease, heal severe lesions and more. Those with wounds that fail to respond to antibiotics could receive a probiotic cocktail adapted to fight the specific strain of infecting bacteria. Body odor could be altered to repel insects and thereby fight malaria and dengue fever. And eczema and other chronic inflammatory disorders could be ameliorated.

According to Julie Segre, a senior investigator at the National Human Genome Research Institute and a specialist on the skin microbiome, there is a strong correlation between eczema flare-ups and the colonization of Staphylococcus aureus on the skin. Segre told me that scientists donât know what triggers the bacterial bloom. But if an eczema patient could monitor their microbes in real time, they could lessen flare-ups. âJust like someone who has diabetes is checking their blood-sugar levels, a kid who had eczema would be checking their microbial-diversity levels by swabbing their skin,â Segre said.

AOBiome says its early research seems to hold promise. In-house lab results show that AOB activates enough acidified nitrite to diminish the dangerous methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). A regime of concentrated AO+ caused a hundredfold decrease of Propionibacterium acnes, often blamed for acne breakouts. And the company says that diabetic mice with skin wounds heal more quickly after two weeks of treatment with a formulation of AOB.

Soon, AOBiome will file an Investigational New Drug Application with the F.D.A. to request permission to test more concentrated forms of AOB for the treatment of diabetic ulcers and other dermatologic conditions. âItâs very, very easy to make a quack therapy; to put together a bunch of biological links to convince someone that somethingâs true,â Heywood said. âWhat would hurt us is trying to sell anything ahead of the data.â

Week Four

As my experiment drew to a close, I found myself reluctant to return to my old routine of daily shampooing and face treatments. A month earlier, I packed all my hygiene products into a cooler and hid it away. On the last day of the experiment, I opened it up, wrinkling my nose at the chemical odor. Almost everything in the cooler was a synthesized liquid surfactant, with lab-manufactured ingredients engineered to smell good and add moisture to replace the oils they washed away. I asked AOBiome which of my products was the biggest threat to the âgoodâ bacteria on my skin. The answer was equivocal: Sodium lauryl sulfate, the first ingredient in many shampoos, may be the deadliest to N. eutropha, but nearly all common liquid cleansers remove at least some of the bacteria. Antibacterial soaps are most likely the worst culprits, but even soaps made with only vegetable oils or animal fats strip the skin of AOB.

Bar soaps donât need bacteria-killing preservatives the way liquid soaps do, but they are more concentrated and more alkaline, whereas liquid soaps are often milder and closer to the natural pH of skin. Which is better for our bacteria? âThe short answer is, we donât know,â said Dr. Larry Weiss, founder of CleanWell, a botanical-cleanser manufacturer. Weiss is helping AOBiome put together a list of âbacteria-safeâ cleansers based on lab testing. In the end, I tipped most of my products into the trash and purchased a basic soap and a fragrance-free shampoo with a short list of easily pronounceable ingredients. Then I enjoyed a very long shower, hoping my robust biofilm would hang on tight.

One week after the end of the experiment, though, a final skin swab found almost no evidence of N. eutropha anywhere on my skin. It had taken me a month to coax a new colony of bacteria onto my body. It took me three showers to extirpate it. Billions of bacteria, and they had disappeared as invisibly as they arrived. I had come to think of them as âmine,â and yet I had evicted them.

– – –

BONUS: Eavesdrop on Julia’s conversation with The 6th Floor blog at the New York Times.

Tags: AOBiome, Bacteria, Bacteria skin spray, Julia Scott, Julie Segre, Lactobacillus, Michael Fischbach, New York Times Magazine, Nitrosomonas Eutropha, No poo, Probiotic cleanser, Probiotic cosmetics, Probiotic FDA regulation, Probiotics, Skin microbiome, Sodium laurel sulfate

Posted in Front Page | No Comments »

The Loneliest Man in Belize

Thursday, May 1st, 2025

‘Rozco! Love you, hon!â cried a man in baggy jeans. His shout, insincere and taunting, was aimed at the back of Caleb Orozco, a 41-year-old man walking along a row of tarp-covered souvenir stands near one of Belize Cityâs ferry terminals. Orozcoâs only acknowledgment was to walk a little faster, car keys clutched in his hand. It was a hot December afternoon, a week before Christmas, high season in the cityâs tourist zone. Two policemen appraised Orozco but said nothing as more taunts flew. âSaw you on TV!â a woman dressed in white jeered from her craft stand, where she sold carved wooden boats. Farther down the sidewalk, two men snickered. âCaleb! You done rub too hard!â leered a man in a blue baseball cap, pointing to Orozcoâs crotch.

âBatiman!â someone called from the shade of a foodÂ-cart umbrella.

In Belize â a small Anglophone Caribbean nation tucked into the eastern flank of Guatemala and Mexico â âbatimanâ (Creole for, literally, âbutt manâ) has long been the supreme slur against gay men, the worst possible insult to their personhood and dignity. But now another slur is beginning to take its place: âOrozco.â

Five years ago, Orozcoâs lawyer walked into the Belize Supreme Court Registry and handed over a stack of papers that initiated the first challenge in Caribbean history to the criminalization of sodomy. Caleb Orozco v. the Attorney General of Belize focuses on Section 53, a statute in the Belize criminal code that calls for a 10-year prison term for âcarnal intercourse against the order of nature.â If Orozco won, his supporters hoped, it would establish a moral precedent across the Caribbean and even create a domino effect, putting pressure on other governments to decriminalize sodomy. But it took three years for the Supreme Court to hear the case; two years later, the nation still awaits a verdict.

In the meantime, Orozco operates the United Belize Advocacy Movement, or Unibam, the only gay Ârights advocacy and policy group in Belize, out of his home in a thick-walled compound on Zericote Street, where stray dogs nose for food scraps in the dirt. The walls are topped with broken shards of glass and rusty, upside-down nails. A seven-foot-tall security gate barricades his driveway. When home, he must remember to lock all six locks â two for his house, two for his office and two padlocks on the gate for good measure. Those precautions do not prevent Orozcoâs neighbor or people walking by his house from throwing rocks and bottles over the walls, shouting, âAala unu fu dedâ (âAll of you should dieâ). Other residents have picked up two-Âby-fours and chased him in the street. People stone Orozcoâs house frequently enough that he rarely bothers to call the police at this point. (This being Belize, a country with a population of just 360,000, he sometimes knows whoever is throwing the rocks on Zericote Street anyway.)

Orozcoâs natural habitat, the place where he feels powerful and at ease, is in front of his pink laptop in his office, a squat outbuilding with barred windows. Inside these walls, no one will disparage his manner of dress: snug graphic tee, stylish camo-print shorts and black Keds that hug his feet like shapely hooves. No one will comment on the way he styles his hank of hair, with a flip to the left and some highlights that tend to come out looking gray. He greets clients and funders with a soft handshake and a wry joke â usually at his own expense. When they leave, he spends hours online in the growing dark, sometimes past midnight.

âDid you know we caused the floods in Belize?â he remarked airily, scrolling through headlines on a local news site. âThereâs an actual comment from a man who says so.â Later he double-Âlocked his office doors and led the way across a yard strung with empty clothing lines, dry grass crackling underfoot. He paused for a few moments, listening for unrest from his neighborâs house, before mounting the heavily sagging steps. He jerked open the sticky door. The floor tipped at an angle, and the ceiling was patched and moldy. One window had holes big enough for him to poke his head through. âMy house is like my life â a hot mess,â he said, making his favorite joke with a wan smile.

He is Belizeâs most reviled homosexual and its most ostracized citizen, a man whom fundamentalists pray for and passers-by scorn; a marked man at 30 paces. His weary face is on the evening news and in newspaper caricatures, which have depicted him in fishnets and heels. His name is now a label, one used to remind other gays that they are sinners and public offenders. Win or lose, Orozcoâs fight for his fundamental rights and freedoms will follow him for the rest of his life.

Americans and Europeans visit Belize for all the things that make âthe Jewelâ an ideal place to relax: coral reefs, paradisiacal white beaches, a green-azure sea. It is a deeply Christian country, with a Constitution that proclaims the âsupremacy of Godâ as a first principle. Recently, it has seen a surge in Pentecostalism and other proselytizing strains of faith. Although bounded on two sides by Latin American countries with more liberal attitudes toward same-sex relationships, Belize retains a culture more closely aligned with Caribbean countries whose perspectives were colored by 200 years of British occupation. There is an ethos of âlive and let live,â but only as long as the gay community remains invisible. Gay couples cohabitate and quietly raise children, but without demanding legal recognition. Couples donât hold hands in public. No hate-crime laws exist to punish targeted assaults.

Formerly British Honduras, Belize gained independence in 1981, inheriting most of its governing documents from its former master. Section 53 is an artifact of Belizeâs colonial past dating to the 1880s. The British bequeathed similar âbuggeryâ laws to all 11 other Caribbean countries once ruled by the crown. (The Bahamas has subsequently removed them.) Buggery became a criminal offense in the England of King Henry VIII in 1533. Of the 76 countries that still criminalize sodomy around the world today, most do so as a holdover from British colonial rule. (Britain repealed its buggery laws in 2003.) In Belize, antiÂgay laws extend beyond the criminal code: Homosexuals are still technically an explicit class of prohibited immigrants, along with prostitutes, âany idiot,â the insane and âany person who is deaf and dumb.â

Much as with Lawrence v. Texas, the case whose resolution in the United States Supreme Court invalidated anti-Âsodomy laws still on the books in 13 states, Orozcoâs challenge is less about sodomy than about discrimination. Even the most zealous Christian leaders, the ones leading the crusade to keep Section 53 on the books, acknowledge that law or no law, sodomy does happen in the privacy of bedrooms in Belize â and not just between gay men, either. Despite the fact that the law is rarely enforced, Orozco and his lawyers say that the threat of indictment encourages public harassment, threats and occasional violence against many gays and lesbians, who have little recourse. The police sometimes charge hush money not to turn people in, according to Lisa Shoman, one of Orozcoâs attorneys. The Belize attorney general told me that he personally believes that Section 53 is discriminatory, though his office is obligated to defend it in court.

Orozco is an unlikely instigator of this challenge. He wasnât politically galvanized until he was 31, when he went to a workshop for gay men and people living with H.I.V. at a public health conference in Belize City. One by one, the men stood up, spoke their names and added, âI have H.I.V.â or âI have sex with men.â Orozco was bowled over. âI got up and said, âBy the way, I like men.â I realized that you perpetuate your own mistreatment by remaining silent. And I decided I would not be silent anymore.â

A year later, he helped found Unibam as a public-Âhealth advocacy group for gay men. Until that point, Orozco had never paid much attention to the H.I.V. epidemic in his country. Even after one of his uncles, who was gay, died from complications related to AIDS, Orozco didnât fully grasp what had killed him. He couldnât acknowledge being gay â to others or himself â until well into his college years. âPeople would ask me, âAre you gay?â And I would say stupid things like: âIâm trisexual. Iâll try anything just once,âââ he recalled. âThe truth was, I wouldnât try anything.â He didnât have sex until he was 23, and when he did, he felt pressured into it. He has never had a long-Âterm boyfriend. The men Orozco knows wonât be seen with him. âThere was one man who would only want me to pick him up after 8 oâclock at night,â he said, rolling his eyes. âI think about it all the time â is this the price Iâm paying? To have no love life? To be the one publicly gay man in Belize? To be the most socially isolated?â

Orozco did not have litigation on his mind at an H.I.V. conference in Jamaica in 2009 when he spoke to two law professors â one Jamaican, one Guyanese â with the University of the West Indies Rights Advocacy Project, which they had recently founded with a colleague to focus on human rights in the Caribbean. They had been studying bans on same-Âsex relationships, laying the groundwork for a test case that, if successful, could encourage similar legal challenges in neighboring countries. Belize was ideal: It had a Constitution with stronger personal privacy and equality protections than other Caribbean countries. From a human rights point of view, it was a case they thought they could win.

When Orozco heard this, he recalled, âI put up my hand â literally â and said: âWhat about me? Iâm ready since yesterday. How can we do this?âââ But even as he signed the legal papers, litigation itself was never the point. âI realized the case was simply a tool to create a national dialogue,â he said. âIt isnât just Section 53. Itâs adoption. Itâs Social Security. Itâs not having the first say of the health of your partner. Thereâs the dignity issues, which havenât been recognized.â

The legal challenge was a controversial move in Belizeâs gay community, where the question of gay rights â what they are and how to get them â is a conversation that has just barely begun. Belize has never had an inciting incident to catalyze a movement, like the 1969 Stonewall uprising. There is no annual Gay Pride parade. No member of government or other prominent figure has ever come out. No gay bars or ritual âsafe spacesâ exist as places for people to meet, just carefully organized house parties and private encounters on Facebook. The L.G.B.T. community in Belize, with the exception of a dedicated corps of organizers and supporters, remains timid, fractured and apolitical. Unibam itself has only 128 members, in part because of peopleâs concern that their names could be made public. âDonât ask, donât tell â thatâs the way with just about everything here,â said Kelvin Ramnarace, a Unibam board member. âIt doesnât mean progress. Itâs one thing to not have rights and know it. Here you think you do, because itâs not so hard to live here. But we donât.â

But Orozcoâs lawyers had reasons to hope that a softening was at hand. The tone had already begun to shift across much of neighboring Latin America, where activists were laying the groundwork for a string of victories. Today, six Latin American countries recognize same-Âsex marriage or civil unions. Eleven countries have banned employment discrimination based on sexual orientation, and seven countries protect L.G.B.T. citizens against hate crimes.

âEven though people said they anticipated some backlash in Belize, almost all the groups I spoke to seemed favorable,â said Arif Bulkan, the Guyanese lawyer Orozco met at the H.I.V. conference. Bulkan and his colleagues spoke to a range of Belizean civil-Âsociety groups and local leaders, including those in the church establishment. He recalled an important meeting with the president, at the time, of the Belize Council of Churches, which encompasses Roman Catholics, Anglicans, Methodists and Presbyterians. âHe said they wouldnât support us openly,â Bulkan said, âbut they wouldnât oppose us either.â

So Orozco had few reasons to think he might regret putting his reputation, and Unibamâs, on the line. Today, he shakes his head like a man in a dream. âI just thought it was going to be some litigation,â he said. âI didnât expect opponents, didnât expect propaganda and all that other stuff that happened.â He paused. âI really didnât.â

In Belize, church leaders are granted deference in the press and by lawmakers on social issues. But in large part, the ecclesiastical focus has always been on the spiritual rather than the political realm. So Orozco was blindsided by the announcement, soon after the suit was filed, that the Roman Catholic Church of Belize, the Belize Evangelical Association of Churches and the Anglican Church had together joined the case on the governmentâs side as an âinterested party,â a legal distinction that allowed them to hire lawyers, file motions and be heard during the trial. More than 400 church leaders and ministries came together to mobilize their adherents in the name of public morality. In another first for Belize, church leaders founded a nationwide activist campaign, Belize Action, and began drawing thousands of believers to rallies that denounced the âhomosexual agenda.â

The churches also flexed their legal muscle in a pretrial motion to remove Unibam as a claimant in the case; as an organization, they argued, it had no standing to challenge the law. Their motion succeeded. Suddenly Orozco was the sole claimant. The case would come down to whether Orozcoâs personal human rights had been violated. He was hounded for interviews, and his name was broadcast all over the world. Someone posted a video to YouTube called â[Expletive] Unibam dis da Belize,â with a photo of Orozco. He received death threats when his name was printed. Shoman, an opposition senator in the National Assembly of Belize as well as one of his lawyers, received explicit rape threats. One day, Orozco was walking downtown, alone, when a man on a bicycle, shouting antigay slurs, threw an empty beer bottle at Orozcoâs head. It smacked him on the jaw and cracked two of his molars. After taking his statement, âthe police said, âIf you find who did this, tell us, and we will pick them up.â Why is that my responsibility?â he asked me with a sardonic smile.

Before the churches joined the case, Orozco allowed three organizations to join forces as an interested party on his side: the Commonwealth Lawyers Association, the International Commission of Jurists and the Human Dignity Trust, major transnational nongovernmental organizations with global standing, large budgets and access to the best human Ârights lawyers in the world. âI thought that using interested parties from the international community would have brought some kind of leverage,â he told me.

But the presence of these foreign groups, even on paper, allowed Orozcoâs enemies to reframe the case as an act of cultural aggression by the global north. According to Bulkan, âa lot of the negative press after that was about foreigners coming in.â Prime Minister Dean Barrow told a local news station: âOne of the things that we have to be grateful for in this country is the culture wars we see in the United States have not been imported into Belize. Well, obviously, this is the start of exactly such a phenomenon.â The United States and Europe were meddling colonizers, Orozco their traitorous pawn. Orozcoâs religious opponents referred to victories for same-Âsex marriage in California and Canada as further evidence of the true agenda at work in Belize. âIt puts a lot of pressure on us,â Orozco said. âWhen we started this, we werenât thinking about gay marriage.â

Opponents made much of the fact that Unibam receives all of its budget, around $35,000 a year, from foreign governments and foundations, including the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives, the Swiss Embassy in Mexico City and the Open Society Foundations. âIs Unibam being used for a foreign gay agenda?â one news station asked. The Amandala, the nationâs largest newspaper, published a page-Âlong editorial under the headline âUNIBAM DIVIDES BELIZE.â âHomosexuals are predators of young and teenaged boys,â wrote the editor in chief, Russell Vellos, in a separate column. âWoe unto us, Belize, if homosexuals are successful in our court. Woe unto us! In fact, since ours is a âtest case,â woe unto the world!â

Six days a week, Orozco drives to his motherâs squat rental in a Belize City suburb and sits down at her glass kitchen table. Perla Ozeata, a matter-Âof-fact woman with the same dark eyes as her sonâs, serves up his favorites: steaming dark bowls of chimole, a Belizean specialty; escabeche with chicken and whole jalapeños; and her special cheesecake. Strangers have cursed her for âencouragingâ her son to be gay, but she is proud of him. The first day Orozco went to court, he wore clothes his mother bought him. She ironed his shirt and tied his tie. Sometimes when she looks at him, she still sees the friendless schoolboy who played in the yard by himself, catching lizards and trying to avoid his bullies and his fatherâs chronic disapproval. She intends to one day tear down the house on Zericote Street and rebuild, so she can move back in with him and protect him. âSomebody have to live with Caleb, because people take advantage of him,â she told me one afternoon. âCaleb no fighter. He can fight out the mouth, but he canât fight physical.â At one point, when Orozco was out of earshot, she said in a low voice: âEvery time he walk the street, they promise to kill him. Win or lose the case, theyâll kill him.â

These days Orozco leaves his compound on foot for only two reasons: to walk to the bank (10 minutes) or to the market for groceries (five minutes). On good days, he can make the 10-minute walk in seven and the five-minute one in three. But even inside a place of commerce, things can go awry. âA gentleman said he wanted to push his bat up my you-Âknow-Âwhat,â Orozco told me at one point. âI was at the bank. I had my nieces with me.â

He was sitting on his messy bed, his knees pressed together. His clothes were jammed into a dresser decorated with peeling childrenâs stickers. Twice a day, Orozco brushes his teeth over the tub because he doesnât have a sink. The walls are a single run of wooden slats with holes like gapped teeth, so pests are a problem. âCompare rats to spiders, and I prefer spiders,â he said.

Coming out is supposed to broaden your world. Orozcoâs world has narrowed to the space between these walls. Some days the tension in his neck hurts so badly that he resorts to painkillers. Other days he just feels numb. He doesnât answer his cellphone when it rings and just watches TV until he drops off to sleep. âI donât like feeling trapped,â he acknowledged. âBut I cannot afford to lose myself in this work. I create my own social space, completely.â

Once in a while he takes a chance on a night out at Dinoâs, a dance club in downtown Belize City. But he never goes without a friend. At midnight one Saturday, Orozco parked near a faded billboard with a picture of a sad-looking woman and the message âABORTION: ONE DEAD, ONE WOUNDED.â With his sister Golda, her husband and a friend, he ascended a narrow concrete stairwell to a long, dark room with earsplitting Caribbean dance music. âThis is what we do,â Orozco said, shrugging. Itâs an in-Âjoke that Belize Cityâs only gay-friendly club is on Queen Street. Drag queens have performed as dancers and singers, but on most nights, like the night we visited, the club is filled with straight couples grinding up against the plywood walls. âNot a lot of gays here,â I said. Orozco replied, âThatâs the challenge.â

There were a lot of watchful eyes at Dinoâs. Camo-clad security guards, grim-faced and armed, scanned the crowd for troublemakers. Hand-painted brontosaurs and stegosauri stared out from the walls, rendered with cartoon menace in Day-ÂGlo colors under black light. As the dancers watched one another, they took in Orozco, taller than most Belizean men at 5-foot-11, as he stood by the door for a long time in burnt-Âorange slacks and natty brogues, sipping a Coke over ice. He watched them back, seeming very ill at ease.

Orozco counted eight members of his tribe in the room that night. He knew all their names, professions and stories. But in four hours, only one, a contractor who had done some work with Unibam, approached Orozco and his group to say hello. Orozco approached no one at all. âI donât have many friends,â he acknowledged later on. âYou turn left, you have criticism. You turn right, you have indifference.â He has warm relationships with his clients and colleagues, but he doesnât socialize.

Ramnarace, the Unibam board member, told me that he supports Orozco as a leader, but that others in the gay community have their doubts. âInternationally, I think he is more accepted than he is locally,â Ramnarace said. âBecause when he says certain things here, he doesnât always come across well.â In interviews, Orozco can appear peevish or overly cerebral, seeming impatient with his interviewer or else resorting to the programmatic lexicon he uses at human rights meetings. âBut still,â Ramnarace went on, âheâs a brave little bitch to go do that, even to fumble. It isnât easy to do, not here, not alone, a little Hispanic guy.â

Orozco used to love going out dancing late at night. One memorable time at Dinoâs, he made out with a man in public, right there on the dance floor. Tonight, he and his small group formed a circle in the darkest part of the room. Golda began to dance in her gold sandals and light flowered dress, smiling at her older brother in an encouraging way. Her husband and their friend danced at her sides. Orozco, expressionless, planted himself near a pillar and began moving in place, gazing down at the floor. âAs long as I donât see an eye looking at me, I can lose myself in the music,â he said. âI just donât want to be conscious of anyoneâs eyes looking at me.â

It has now been 24 months since the hearings on Section 53, with no word on when Chief Justice Kenneth Benjamin will deliver a decision. The Supreme Court does not have a calendar for decisions, and sources close to the case have refused to speculate as to the cause of the unusual delay. The Supreme Court Registry did not answer a request for comment. âUnfortunately, civil matters in this country do proceed at a very slow pace,â Shoman said. âBut I could never have imagined that something of this magnitude, a case regarding the personal liberty of the citizens, should take so long.â She and the rest of Orozcoâs legal team have sent multiple letters to the registrar general but received no reply.

Jonathan Cooper, the chief executive of the Human Dignity Trust, is just as eager for results. âThe ramification of the Belize decision will be felt across the Commonwealth, if not beyond,â he told me. Because either side is likely to appeal any decision all the way to the Caribbean Court of Justice, the highest court for not only Belize but also Barbados, Dominica and Guyana, the controversy (and Orozcoâs notoriety) is likely to spill over into those nations as well. And then there is the matter of international human rights law. The legal groups invoked the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights in their argument, with the knowledge that should the appeals court rule in Orozcoâs favor on that basis, other jurisdictions would find the criminalization of sodomy very hard to justify.

After waiting so many years, Orozco has made a decision of his own. Shortly after the court hearings, he quietly stepped down as the president of Unibam. He stayed on as its executive director, but he told me that he hopes to leave that post next year. âIâve come to realize that Iâve sacrificed my life to this work,â he said. âAnd I wake up to an empty bed and a pillow. And what does that say about me?â

These are not the words of a Harvey Milk revolutionary, and in fact Orozco doesnât see himself in the mold of Milk, who was murdered at 48. But Orozco has believed for some time now that he wonât outlive his middle age. âMy larger goal is to survive to the end of my case,â he said. âThey said that if something should happen to me, the case would be over. Iâve invested seven years of my life in this thing, and I donât want to throw that away.â

Orozco has come to the conclusion that the big changes he thought were within reach five years ago are actually a generation away. Living in Belize as a gay man or woman is like peering across a demilitarized zone with a pair of binoculars. If he took a four-Âhour bus ride to Chetumal, Mexico, Orozco would enjoy the right to marry. Someday, Orozco may tear down his house and rebuild it. He may go to law school or pick up the business-administration career he left behind. But he has ruled out leaving Belize. He loves his family too much. He hopes that with time, most of his fellow Belizeans will learn not to judge. âOur opponents have been fear-mongering,â he said. âMost people could care less what I do in my bedroom.â

One afternoon, Orozco took his least favorite walk, to the bank. He rose from his office chair, turned off the fan, cut the lights, locked all six locks and stepped out in a brown tie-dye button-down and kneeÂ-length cotton pinstripe shorts. The narrow downtown streets were clogged with cars short on mufflers, long on horns. He passed bakeries and pharmacies and street vendors hawking bags of peanuts and dried fruit and discount clothing stores blaring pop music.

Stoop-Âsitters on Central American Boulevard nudged one another and gestured. A man in a truck driverâs uniform, smoking a cigarette, quietly watched Orozco go by, then spat and uttered a profanity. Two adolescent girls turned to look back at his retreating form, then doubled over with laughter. Three construction workers, legs dangling in a muddy trench, looked up as Orozco walked past. âHey, Belize bwai!â they shouted. âHoo da fayri, butt bwai?â

A few steps from the bank, Orozco passed two women alongside a young girl with her hair tied back in braids, wearing gold sandals and a flouncy white dress. She gazed at Orozco with curiosity. Then she looked up. âMama,â she said, âthatâs a batiman.â

Tags: anti-gay, Belize, Belize Action, Belizean, buggery, Caleb Orozco, Caribbean Court of Justice, Caribbean gay rights, gay and lesbian, Julia Scott, LGBT, New York Times Magazine, Scott Stirm, section 53, sodomy law, Unibam

Posted in Front Page | No Comments »

Letter of Recommendation: Candle Hour

Tuesday, March 18th, 2025

One of my best teenage memories starts with a natural disaster. In January 1998, my parents and I returned to our home in Montreal to find that a giant tree limb had ruptured our living room. What would soon be known as the Great Quebec Ice Storm had struck. It was the most catastrophic in modern Canadian history. Accumulations of freezing rain had cracked our maple tree nearly in half. It shattered our front window, glass fringing the tree limb like a body outline in a murder scene.

Outside, downed power lines sparked like electric snakes. More than a million Quebecers were left without power. Cars were crushed and impaled by fallen limbs. Because the ice could inflict violence at any moment, everyone retreated indoors, making for an oddly quiet state of emergency. Except for the distant beeps of electrical-crew trucks, all you could hear was the crack of trees buckling under the weight of the ice, day and night. Long after the sidewalks were cleared, we tiptoed past the eaves of tall buildings and kept our voices low, steering clear of icicles thick as baseball bats and sharp as spikes, primed to fall at any moment.

For seven days and seven nights, until the power returned, we lived by candlelight. We learned to be mindful of candles: how to stand them up, walk with them, nurture their light. At first it was maddening to cook dinner â to carefully carry a plate of candles to the cupboard, poke around for ingredients, then go off again in search of a knife, taking care not to drip wax into the cutlery drawer. I learned how to brush my teeth and bathe by candlelight; the light bounced off the mirrors, making the bathroom for once the brightest room in the house. In our bedrooms, we piled under blankets and read ourselves to sleep by the flickering flames.

Outside, our neighborhood descended into darkness at twilight, but if I stared hard enough at windows blurred with ice, I could just make out little dancing lights. Decades later, no one in my family remembers what we talked about, or ate, or how we spent our afternoons that week. But we all remember the candles.

The Montreal Ice Storm, 1998. (Archives de Montreal)

Iâve since settled in California, and last January events in the world left me with a hunger for silence. I adopted a strict information diet: no television news or social media. One evening, I didnât even bother to flick on the lights in my apartment. I walked quietly to the window and watched the last of the day, the darkness swallowing the trees along my street. Instinctively, I went looking for a book of matches in the back of the kitchen junk drawer. Opening a closet, I felt around until I discovered the remnant of a housewarming gift: a milk-white candle. I struck a match and lit the dusty wick. I commandeered a plate from the cupboard and set it on my coffee table. I nestled in a blanket, listening to the wind in the courtyard. Eventually, for the first time in too many days, I found myself surrendering to sleep.

That was the start of a practice Iâve taken to calling Candle Hour. An hour before I go to bed, I turn off all my devices for the night. I hit the lights. I light a candle or two or three â enough to read a book by, or to just sit and stare at the flame, which, by drawing oxygen, reminds me I need to breathe, too. I surround myself with scents and objects I like â some fresh rosemary plucked from a neighborâs bush, a jar of redwood seed pods. I have a journal ready, but I donât pressure myself to write in it. Candle Hour doesnât even need to last a full hour, though; sometimes it lasts far longer. I sit until I feel an uncoupling from the chaos, or until the candle burns all the way down, or sometimes both.

Candle Hour has become a soul-level bulwark against so many different kinds of darkness. I feel myself slipping not just out of my day but out of time itself. I shunt aside outrages and anxieties. I find the less conditional, more indomitable version of myself. Itâs that version I send into my dreams.

At night, by candlelight, the world feels enduring, ancient and slow. To sit and stare at a candle is to drop through a portal to a time when firelight was the alpha and omega of our days. We are evolved for the task of living by candlelight and maladapted to living the way we live now. Studies have noted the disruptive effects of nighttime exposure to blue-spectrum light â the sort emanated by our devices â on the human circadian rhythm. The screens trick us into thinking we need to stay alert, because our brains register their wavelength as they would the approach of daylight. But light on the red end of the spectrum sends a much weaker signal. In the long era of fire and candlelight, our bodies were unconfused as they began to uncoil.

Tonightâs candlelight will cast the same glow on my Oakland walls as it did on my parentsâ walls in Montreal in 1998. Iâll feel in my bones that the day has passed â as all days, even fearful ones, eventually do. The dayâs last act is cast in flickering gold. Iâll watch the flame bob and let my mind wander, until I realize Iâm sleepy. After a while, Iâll lean over and blow it out, ready now for darkness â where renewal begins.

Tags: Candle Hour, Julia Scott, Letter of Recommendation, New York Times Magazine, Queben ice storm

Posted in Front Page | No Comments »

My Bed Runneth Over

Saturday, February 15th, 2025

âSo are you guys in an equilateral triangle, or are you more of a V?â

A dark-haired woman leans over to an eager-looking young couple seated next to her and holds up her thumb and forefinger. Each of the V signifies a person; the fleshy connective tissue between them stands for the partner to whom they’re both sexually connected. Her hand gesture is intended as an icebreaker, but the couple pause awkwardly, as if they don’t know exactly how to answer.

In polyamorous relationships, knowing where you stand is crucial, but often hard to figure out. Whether you have 2 partners or 10, managing multiple liaisons can feel like walking a tightropeâwhich is perhaps why the perplexed couple have come to this unmarked warehouse on Mission Street that houses the Center for Sex and Culture. Tonightâs Open Relationship Discussion Group is exploring âThreesomes and Moresomes.â The attendeesâa total of 22 men and women, a commendable turnout for a Monday night in Novemberâsit in a neat circle, jittering with the same blend of excitement and anxiety that you might find in a roomful of people training for their first parachute jump.

Coats still on against the chill of the unheated room, the gathered polyamorists try not to stare too obviously at the painted nudes on the wall, rendered in various poses of masturbation and frottage. Itâs a hip-looking crowd, mostly in their 30s and 40s, white, and flying solo, though there are a few couples and one triad: two women and a man who stroke each otherâs hands and listen, but never speak.

When Marcia Baczynski, a relationship coach and tonightâs discussion leader, asks how many people are new to the group, nearly half raise their hands. Some of them are new to poly altogether, including one smartly dressed woman who met the love of her lifeâa married manâon OkCupid six months ago. With his wifeâs consent, she and the man started a passionate affair. Little by little, the two women grew to care for each other as well, to the point that the three of them now sleep in the same bed.

âIf I hadnât fallen in love with him,â the woman says, âI wouldnât have been able to develop feelings for her. Theyâve been together 17 years, and sometimes I see them as the same person.â She gestures toward the man on her left, who smiles and takes her hand. Then her face falls: The wife, who is not present tonight, is pregnant. âThereâs this other large need that I have,â the woman confesses, âto get married and have kids. Thereâs a huge guilt in me for wanting to date other men. Iâm afraid Iâll hurt him if I do.â She starts to cry. The room is silent until the man speaks up: âIâve told her that the last time I loved someone this much, I married her. I donât know what to do with this.â

Someone asks whether the two of them have talked about having a child together. They have, and they may. âBut thatâs the hard part for me,â the woman says. âItâs so not what my parents wanted for me. Itâs not the social norm.â Everyone nods.

âJealousy, time management, and lack of clarity around what youâre doing.â Baczynski ticks off the three most common pitfalls that beset practitioners of poly. Weâre seated close together on a lipstick-red velvet chaise at Wicked Grounds, a kink-friendly cafĂ© on Eighth Street where you can purchasee hand-carved rosewood butt paddles with your peppermint tea. Curly-headed and bright-eyed, Baczynski exudes friendliness that inspires a tangible intimacy. A decade ago, she gained fame in the alt-sex community as the coinventor of cuddle parties, which began in 2004 with clothed strangers caressing each other in her Manhattan apartment and have spread to thousands of living rooms across the United States and Canada. Now she’s one of the Bay Area’s most sought-after relationship coaches in the poly sphere, thanks in part to the prominence of her online curriculum, Successful Nonmonogamy, which helps couples open up their relationships without imploding them.

Twenty-four years after Sonoma County pagan priestess Morning Glory Zell-Ravenheart conceived the word âpolyamoryâ (meaning âmany lovesâ), the Bay Area poly scene is still the biggest in the country and very much in the vanguard of a movement to disrupt monogamy. Many of its members are more aptly described as âmonogamish,â Dan Savageâs term for couples who stay committed to each other while having sex on the side. (Polyamory also extends to couples who date each other and single people who date around a lotâalthough poly types tend to dismiss cruisers and commitment-phobes as not part of their tribe.) But the variations only spin out from there. The aforementioned V becomes an equilateral triangle when a threesome commits to sharing sex, love, and face time among all three partners. Two couples, or a couple and two singles, make a quad. If a fivesome is connected via a common partner, thatâs a W. Partners may be primary, secondary, or tertiary, though some polys reject those terms as too determinative. A distinction is made between lovers and metamours (a partnerâs partner), the latter often a close friend who steps in to resolve conflicts, cook dinner for everyone, and help raise the kids.

The concepts behind these words are constantly being hashed out in homes throughout the Bay Area, long known as polyamoryâs petri dish. New additions to the vocabulary often bubble up here before filtering out to polyamorists in the rest of the country. âCompersion,â for example, defined as taking pleasure in your partnerâs pleasure with another person (the opposite of jealousy), emerged in the Kerista Commune, a Haight-Ashbury âpolyfidelitousâ social experiment that used a rotating schedule to assign bed partners.

Dossie Easton, a Bay Area therapist who wrote the landmark poly bible, The Ethical Slut, in 1997, gets emotional when she talks about how far the poly world has come since her arrival here as a sexual revolutionary in 1967. âI see people who start out where I fought for years and years to get to. They think that they should be able to come out to their families, that their parents should accept them and welcome all their various partners and their various partnersâ children for Thanksgiving.â

This isnât the polyamory of your imagination, filled with â70s swinger parties and spouse swapping in the hot tub. In fact, the reality of polyamory is much more muted, cerebral, and, well, unsexy. Generally speaking, self-identified poly types arenât looking for free love; theyâre in search of the expensive kind, paid for with generous allotments of time and emotional energy invested in their various partnersâand their partnersâ children and families. All of that entails a lot of heavy lifting, and a lot of time-consuming sharing. âThereâs a joke,â Baczynski says, laughing: âSwingers have sex, and poly people talk about having sex.â

If it all sounds inordinately complicated, thatâs because it is. What do you do when your partner vetoes a potential lover? How do you handle it when your spouse starts dating your ex? To cope with jealousy and the thorny subject of sexual boundaries, the poly community relies on an excess of communicationâhence, discussion groups like tonightâs. The community calendar offers nonstop opportunities for support, conversation, and debate, including potlucks, workshops, coffeehouse socials, political discussions, and book readings. As one woman tells me, people here like to geek out on relationship philosophy as much as they like to geek out on software (and, in fact, the polyamory world has considerable overlap with the tech community).

In the poly world, uncoupling monogamy and sex leads not only to casual sex but also to uncasual sex and, sometimes, uncasual unsex (that is, ritualized cuddling). âI have the freedom to do whatever I wantâand what I want includes taking on a lot of responsibility,â says Baczynski, who is in long-term relationships with one woman and two men. Polyamory isnât about destroying a beloved institution, she argues. Instead, itâs about casting people in the roles that they actually want to play. âThereâs an assumption in our dominant culture that the person youâre having sex with is the person who has all the status and has the mortgage with you, too,â she says. âWhy do sex and mortgages go together? Iâm not sure.â

But freedom comes with a multitude of challenges, many of which were voiced by the following sampling of local poly practitioners. Collectively they provide a glimpse of what itâs really like to be âopen.â

Gloria and Alex and Luna and Joe

Gloria Schoenfeldt wasnât particularly drawn to polyamory, just to people who happened to be polyamorous. First the 31-year-old school-teacher got used to having a polyamorous best friend in Luna Murray, a 25-year-old event planner. Hearing of Lunaâs sexual adventures may have made it easier for Gloria to open her heart to a man named Alex, a 45-year-old photographer and relationship coach who identifies as not only poly but also pansexual.

At first, Gloria didnât want to know about Alexâs other liaisons, other than their namesâshe couldnât take the details creeping into her imagination. But that changed when she realized that she wanted to be a part of his âjoys and sadnesses,â even if they werenât with her. âItâs always worse in my head than it is in real life. Itâs always bigger and scarier and more intense and more likely to cause the end of our relationship,â Gloria says. Now she comforts Alex through breakups and heartachesâand enjoys dating other men as well.

When Gloria introduced Alex to Luna, she was happy to see that they hit it off. The couple also got along well with Lunaâs boyfriend Joe. So well, in fact, that eventually they all became lovers. Last February, the two couples decided to cohabitate, renting a two-bedroom apartment in Berkeley. For the first time in her 31 years, Gloria tried on the poly lifestyle in earnest, taking care to schedule her dates at the same time as Alexâs so as not to feel abandoned. She shares an occasional sexual four-way with her husband and housemates (they call their state of emotional intimacy a âquasi-quadâ). Most of the time, though, theyâre plain old housemates, two linked couples who pool money for groceries and get into tiffs over keeping the house tidy. âWe live together, we have this loving family connection, and I donât know what to call that,â says Alex.

Does it work? It does for nowâone year in is too soon to declare it a permanent success, although the couples are talking about having children of their own. And both couples married last July, in jubilant back-to-back weddings in Orinda and Berkeley (they served as each othersâ witnesses). What keep things stable are the poly-relationship standbys: limits and communication. While they sometimes couple off or have collective sex in the same room, itâs not an orgiastic free-for-all. There are boundaries. Gloriaâs never had one-on-one sex with either Luna or Joe. When dating outside their marriage, Alex and Gloria only have protected sex. Luna and Joe wonât bring home a date who hasnât been vetted by their respective spouse, as well as by Alex and Gloria. Everyone keeps a lid on when Alexâs 12-year-old daughter from a previous relationship comes to stay, although she knows that her dad is poly and has seen him kissing his housemates in a non-housemate-like way.

Still, the arrangement has its challenges. Joe, a 25-year-old server at an upscale Berkeley restaurant, used to get so jealous of his wifeâs lovers that they developed a system: Before she left on a date, she would sit him down and tell him all the things that she loved about him and promise him that she was coming home. Over time, âit got easier and easier,â says Joe. Now the tables have turned. Joe has several lovers, while Lunaâs sex drive has plummeted. Itâs made her insecure and sad. âI used to be this sexual beast, and Iâm feeling very fragile about my sexuality and my body…. Heâll talk about how much he loves his partnerâs body, and Iâll start crying,â she says.

But as far as Gloriaâs personal plunge into poly goes, she considers it a success. She was skeptical of monogamy prior to meeting Alex (âIt doesnât provide the security it claims to, because it canâtâ), but had questioned whether she had the emotional capacity for an open marriage. Seven months in, the answer is yes, this is a good life. So far.

âThe abandonment stuff still comes up,â Gloria says. âWhen that happens, I cry. And we talk. And he holds me and he reassures me.â

Ian

Ian Baker became a practicing polyamorist the hard way: He fell in love with a girl who told him that she didnât want to be monogamousâand then slept with his housemate. âI freaked out,â recalls Baker, but he wanted to be with her nevertheless. âI had to do a lot of work for it to be OK,â he says, âfor my particular psyche to be OK with it.â

That he faced such a difficult adjustment was surprising to Baker, for whom polyamory was hardly a new concept: Heâd grown up in a poly family with three parentsâhis dad, his mom, and his dadâs girlfriendâwho bedded down together every night. They were poor, living in a small cottage in the woods in Sonoma County. Baker, who believes that the arrangement helped keep them all housed and fed, likes to use his story to counter the perception of poly as the domain of oversexed, affluent people with way too much time on their hands. âWhen I was a kid, my parentsâ relationship made perfect sense,â he says. âWhatever situation you grow up in is the situation that makes sense.â

Baker, a developer and CEO of the Y Combinatorâbacked startup Threadable, describes his younger self as an insecure fellow who looked to his girlfriends for validation. He started reading books about jealousy, and slowly it dawned on him that polyamory could help him outgrow his core anxiety. And so he tapped into the poly community for emotional support. âThe only reason that I ever wanted monogamy,â he says now, âwas because I was insecure.â

Baker is in love with Lydia (not her real name), his partner of four years. He doesnât date much outside the relationship, he says, because heâs basically fulfilled. âBut that doesnât mean I want to be monogamous,â he quickly adds. âI like the connections that exploring sexuality brings to my life.â

Lydia, on the other hand, does have other lovers. âShe wants to see other people, and I want her to have what she wants,â Baker says. But every time she takes a new lover, he admits, âI have some anxiety. So when thatâs the case, I have to do a little work. Iâll call someone and chat with them about it for a few minutes, and then Iâll feel better. Itâs not a big deal.â

For poly practitioners like Baker, self-improvement and sexual exploration are overlapping preoccupations. Itâs well-nigh impossible to handle the emotional agitation of concurrent relationships without facing oneâs own self-relationship, they sayâyour resilience must be equal to the task. âThereâs a bunch of different ways that you can learn to be emotionally self-sufficient, and it happens that I learned those lessons by having my girlfriend sleep with my friends,â says Baker, chuckling. âBut since then, itâs been wonderful.â

Sherry

Bespectacled and wearing pink yoga pants, her hair wet after a shower, Sherry Froman leads me up the rainbow staircase to her bedroom and stretches out on her cozy sheepskin rug like a cat in the sun. She has hosted play partiesâfeaturing touching and, sometimes, sexâfor years on these sensuous carpets, beneath tapestry-draped ceilings that evoke four-poster beds. Some of the parties begin with an opening ceremony that resembles a personal-growth workshop: Participants practice communicating boundaries and desires, gaze into each otherâs eyes, reveal the body part that they want to be touched, practice saying yes and no, explore the mattresses laid out on the floor. But, Froman hastens to add, ânot everything is like thatâNew Age, woo-woo spirituality. The poly scene is very diverse.â

When Froman falls for someone new, someone she wants to date for a while, she skips the elaborate lingerie and whips out her calendarânot because she wants to keep her multiple suitors from colliding, but because she wants them to meet. If they form a copacetic bond, she believes, someday they all might cohabitate in the big house that, for now, resides solely in her imagination. That dream was a reality once, 20 years ago at Harbin Hot Springs, just north of Napa ValleyâFroman would walk from house to house visiting friends and lovers who were studying tantric techniques and the full-body orgasm. âI was 23, and all these older men wanted to pleasure me and were fine with me not giving anything back,â she says. âI thought, thatâs different from college boys.â

Since then, Froman has dated her share of supposed polys who hypocritically wanted their women to be monogamous with them. âI think a lot of men have a difficult time with polyamory, because the fantasy looks nothing like the reality,â she says. âBecause if a man has several female lovers in his life, chances are that the women are going to talk about him to each other. And theyâre all going to want him to be comfortable talking about his feelings.â

In the two decades since her time at the hot springs, Froman has learned to resist the pull of NREâthatâs ânew relationship energy,â a poly term for the fizzy bubble of endorphins that envelops the newly besotted. While NRE feels great, she says, the high highs usually lead to the opposite. âYouâve got to think sustainably,â she says. âHow is this person going to work for you over a period of time?â

Froman describes herself as having been a âveryâ sexual person since puberty. (When she decided to lose her virginity at age 16, her mother reserved a honeymoon suite with a heart-shaped Jacuzzi for the occasion and took her lingerie shopping.) After years of casual encounters, she stumbled onto the poly world and started choosing partners for different reasonsâlove, friendship, community. But lately she has again been hankering for more male partners in addition to the long-term beau with whom she shares this four-bedroom in Glen Parkâitâs called âadding on.â

Froman, who met her live-in boyfriend on OkCupid (where users can self-identify as nonmonogamous) more than five years ago, believes that her schedule could support three other live-in men. But how to find them? She used to make promising friends by hosting Open Relationship Community potlucks at her house, but now sheâs trying to explore new social venues to unearth men. âOnce I find them,â she says, âthen all of us being in the same bubble with each other is going to be a lot easier. Itâs like having a family.â

William and Anna

Anna Hirsch thought that William Winters was going to be her first one-night stand. She ended up marrying him. When they met in Baton Rouge, their relationship stylesâhis casual connections, her commitment to monogamyâseemed as mismatched as their temperaments. Then they discovered poly, which squared their deep, if idiosyncratic, love with their desire to avoid the mistakes of relationships past. They agreed to experiment, and when Hirsch left town for several weeks, Winters slept with someone else. He didnât tell Hirsch until she got back.

âShe cried for two consecutive weeks,â recalls Winters. âIt was totally fucking horrible. I remember saying, âAnna, if it is this hard, we do not have to do this.â It was she who said, âNo. There is something in this for me. Iâm choosing this. But we cannot do it your way.ââ

Eight years later, Hirsch, a writer and editor, and Winters, a progressive activist and organizer, are one of the most socially conspicuous poly couples in the Bay Area. In honor of the poly potlucks that they organized for a time, the Chronicle went so far as to dub Winters the âde facto king of the East Bay poly sceneââif you ask, heâll show you a playing card, designed by his friends as a joke, that depicts him as the king of hearts.

Hirsch and Winters live in the Oakland Hills, in a studio apartment attached to a house occupied by several other poly couples. These days, Winters hosts private play parties and enjoys mingling with women. Hirsch is in a four-year relationship with a married couple (sheâs more serious with the husband than with the wife) and has a boyfriend as well. Doing things Hirschâs way means that Winters has the freedom he needs to play, while she puts down roots with the people she loves. Although sheâs legally married to Winters, she likes to âproposeâ to her partners as a way of acknowledging their importance to her. When she mock-married a platonic friend back in Baton Rouge, Winters was her date to the wedding. âI have this whimsical image of myself old on a porch somewhere, someday,â Hirsch says. âAnd I would like William to be on that porch. And I think it would be amazing if there were other people on that porch, too.â This processâfitting together relationships without elevating them or putting them in special categoriesâis described by the couple as âintegrating.â

So why did they marry at all? Winters frowns. âI feel like that question itself comes from a scarcity model that says we only have time for one major relationship. That kind of underlies the dominance of monogamy.â Hirsch has a more practical answer: They were in love, and she needed health insurance. âBut what do I care about what marriage means?â she says. âItâs not a promise. Itâs a celebration of whatâs possible.â On their wedding day, she and Winters nixed vows and simply made a toast.

On the poly success scale, Winters rates their relationship as a 9.8 out of 10. Jealousy? Never a problem. Boundaries? The coupleâs only rules concern safe sex and date disclosures (each a must). Even so, their marriage has been shaken this past year by the same temperament and communication problems that have plagued them since they got togetherâat one point, they put their chances of splitting up at 50-50. For all its laboriousness, polyamory is a deeply gratifying lifestyle for Winters and Hirsch, and the effort that it requiresâthe sometimes Augean task of maintaining multiple messy arrangements all at onceâis more than paid off by the emotional rewards. Still, the day-to-day upkeep of a relationship can test anyoneâs fortitude. âThe poly stuff? So easy,â Winters says. âAnd the rest of it is like, sometimes, why does it have to be so fucking hard?â

Tags: Bay Area sex parties, cuddle parties, Dossie Easton, group sex, Julia Scott, Kerista Commune, Marcia Baczynski, Polyamory, San Francisco, San Francisco Magazine, The Ethical Slut, Wicked Grounds, William Winters

Posted in Front Page | No Comments »

How Quebec Separatism Prepared Me for Trump’s America

Thursday, February 6th, 2025

My sense of belonging to Canada came at the moment I was faced with the prospect of losing my place in it. The night of October 30, 1995, my parents held a gathering for thirty friends to watch the Quebec referendum returns on TV. Outside, the Montreal night fell quickly and very few of us spoke, ate, or breathed. I was fifteen years old.

The vote teetered over the line between Yes and No for hours. When the results broke for the No campaign, it was by such a small marginâ54,288 votesâthat we experienced more a sense of relief than of victory. The federalist vote had won, and my family, their friends, all of us Anglophones had affirmed our right to stay in Canada. But 2.3 million of our neighbours had betrayed us. Thatâs how it felt at the time: we were surrounded by people whoâd decided their enfranchisement, their identity, precluded ours.

Quebec would remain tethered to Canada, but unbeknownst to me, my parents made a different decision that night. Across the room, their eyes met; there was no need to speak or negotiate. It was time for us to go. My parents felt that as Anglos, Quebec had no place for us. The moment high school ended, we moved to California.

Those years in Quebec, âIt was like the country you thought you were living in was no longer your country,â remembers my mother. There could be no better way to sum up my own feelings, and those of millions of fellow Americans, after the election of Donald Trump. Coping with the aftermath has split my American friends into two camps. One group is in the fight. They protest, sign petitions, binge-donate to non-profits, and call Congress members every day. Others have turned off the channel completely, booking last-minute trips to Mauritius, Costa Rica, and other faraway places with little Internet access. Fellow writers have told me they are in âinternal exile,â a term invoked by artists who stayed in Germany during the Nazi occupation. They work on whatâs in front of them. They donât engage beyond it.

And then thereâs the #Calexit crusade, which evokes an unpleasant sense of dĂȘja vu. Although the effort to have California secede from the union and gain independence for the worldâs sixth-largest economy is still a fringe movement, it has gained some powerful backers in the tech sector. Proponents have already filed language for a proposed referendum in March 2019. Itâs a long shot: even if a majority of Californians voted for it, enacting the legislation would require an amendment to the US Constitution and the approval of both chambers and thirty-eight states.

But itâs a sentiment I understand all too well.

Let me be clear: I reject separation completely. There is no way you can convince me that anything could justify being legally separated once we are bound together as a country. But based on my experience in Quebec, I find myself wanting to warn my fellow Blue Staters that thereâs a deeper process we need to undertake: that of emotional resettlement, of finding a new whole to identify with.

Canada stayed together after 1995, officially. But Quebec never ended its emotional journey to define how it belongs to the country, and how it belongs to itself. I went on a similar journey. I still have (and cherish) my Canadian passport, but my loss was permanent. My status as an emotional refugee began with the referendum, and our plans to leave. But it didnât end until Iâd traded my sense of belonging in Quebec for a sense of belonging in California.

We Blue Staters are now the emotional refugees, millions of us. We lost this election, and a lot more besides. We lost our illusions of belonging to a fractious but inclusive America. The one that honours individual freedoms and a form of governance grounded in our collective common values. Like kindness. Donât forget kindness.

*

The fact is, sometimes your side loses an election. Thatâs part of the process. But this time, weâre not just on the losing side: weâre on the outside. This country we loved and believed in has left us. What do we belong to now? Over the next four years, there are aspects of the culture weâll leave behind, walk away from, just as we feel it has rejected us. But some things are left that weâll need to walk toward.

Geographically, of course, we are staying put. But emotionally, we are divested. Where will we find our new homes?

Weâll need to find them in ourselves. And for that, I look toward Quebec.

Tens of of thousands of Anglophones left Quebec after 1995, just like my parents and I. But lately I have been thinking about the peopleâfriends and family includedâwho stayed behind to participate in a civil society that is still very much at odds with itself.

The referendum campaign was my political awakening. I was old enough to grasp the stakes, and for the first time, I felt like I was part of something bigger than myself. I remember the historic Unity Rally in the Place du Canada. My classmates and I skipped school and walked downtown, where I tried to perch on a stack of unwieldy police barricades and catch a glimpse of the leaders on the dais. I remember Jean Charestâs curly Afro, the buses of waving Canadians from other provinces and the enormous flag the crowd held on its shoulders, as big as a hundred flattened parachutes.

On the night of the 30th, after the votes were counted, I sprinted onto Sherbrooke Street with a friend, shouting and waving a Canadian flag. Many drivers honked in support; some yelled abuse.

Now I think back to that night and imagine the devastation and the loss for all the people who were so sure history would go another way. They, too, were motivated by wanting to belong. I can see how, having touched the dream, watching Jean ChrĂ©tien declare victory on TV must have felt as dejectedly surreal as it still does when I turn on the TV today and see the words âPresident-elect Trump.â

Quebec nationalists voted with their hearts, not with their headsâso went the narrative at the time. I have heard that patronizing description applied to some of the people who voted for Trump, too. But if it is true, then it only reinforces my belief that now is not the right time to change hearts and minds in America. Painful as it is for a liberal artsâeducated journalist to admit, there are limited possibilities for dialogue in a climate characterized by either recrimination or retreat. But it is possible to try something else.

Iâve lived outside of Quebec for eighteen years now. Sometime after I left, QuebecersâFrancophones, Anglophones and Allophonesâgot to work creating a society they felt they could belong to, whatever the passport. There were some major moral failures at the government level (the Quebec Charter of Values comes to mind), but Iâve also seen major progress toward integration, regardless of political beliefs. Many of my Anglo friends now work in French all day. Theyâve married and befriended French Canadians. Their kids are growing up bilingual in a distinct, multicultural society. When I visit Montreal, I feel more comfortable in my own skin than I ever did growing up.

Thatâs the feeling I want for this country. And it wonât come from turning our backs on the federal government. The wisdom of separatists was not in the instinct to leave; it was in defining exactly which values mattered to them, and using those values as a template after the referendum to find a way to belong inside Quebec, and also inside Canadaâfor now, at least.

We will all live in Trumpâs America, but that doesnât mean we should back down from the challenge of living the way we want our society to function. No one can take those values away from us. They transcend us and, ultimately, define our neighbourhoods and local institutions.

The harmony in Quebec may be illusory. If certain politicians have their way, someday my friendsâ children may also find themselves voting in a shattering separatist referendum. And theyâll need to confront the same questions of allegiance that we did. But by then, concepts of âusâ and âthem,â âinsiderâ and âoutsider,â may have changed.

I now know that staying is one thing, belonging another. After I left, Quebecers built a society that holds hope for the latter. Itâs still a fraught and emotional experiment. But itâs a feeling we Blue Staters will need to get used to.

Tags: #CalExit, Blue States, Multiculturalism, politics, Quebec referendum, Red States, separatist movement, Trump

Posted in Front Page | No Comments »

Pesticides indicted in bee deaths

Saturday, May 18th, 2024