Posts Tagged ‘Julia Scott’

The Panic Button

Wednesday, January 1st, 2025

When I think about how we come to fear, I think about a photograph my parents took of me as an 11-year-old. Iâm in their bedroom, perched on the edge of their bed. Itâs plenty warm in the house, but Iâm dressed for subzero temperatures. I have on layers of clothes underneath my wool winter coat. I wear a bright pink ear-warmer headband above my ponytail and glasses, through which I stare out at the camera with a baleful expression. I am clutching a fire extinguisher.

I remember that my parents thought I looked adorable in my getup as I prepared myself for a notable first: They were leaving me alone, without a babysitter, to go out with their friends for the night.

They naturally assumed I would eat the dinner theyâd prepared, watch some TV and go to bed. I naturally assumed that something would cause the house to catch fire and, despite my attempt at heroics with the fire extinguisher, I would end up in the snow outside, watching it burn.

I spent much of that evening on their bed, waiting for them to come home, the fire extinguisher propped up on a pillow next to me. Every so often Iâd peer into the snowy street to see whether any strangers were approaching our front steps. I scurried upstairs and downstairs, my heart pounding, as I listened for sounds that seemed out of place â anything that could be construed as the first signs of a burglar who, I was sure, would choose this exact evening to try to break in. Whenever the refrigerator switched on or a truck rattled by, I jumped.

To say I was a needlessly fearful child is accurate, but it also diminishes the reality of my dread. I was certain that something bad would happen â soon â to me or to the people I loved. When my parents left me at home, Iâd tell myself terrible stories that initially seemed plausible, then seemed inevitable, and then didnât seem like stories at all â panic-inducing scenarios of my parents being assaulted on the street or getting into a car accident. The feelings produced by these fake storylines felt real. I was scared, and therefore I had reason to be. That was the feedback loop.

My mother would try to help me see my fictions for what they were by offering an alternative ending. She would stop what she was doing, sit me down and detail how safely their evening would play out, from dinner at the restaurant to the play they would see afterwards. She would never, to my frustration, commit to a curfew.

Frequently, she reassured me by pointing out the little doorbell installed on the left side of her bed. It was round and white to blend in with the rest of the wall and positioned about a foot above the telephone. The panic button, she called it. One push and it called the alarm company. The police would come to the house. Only use it in an absolute emergency.

This only confirmed what I had suspected: I had legitimate reasons to panic. I timed how long it would take me to run down the hallway from my bedroom and push the panic button. Sometimes at night I would creep toward my parentsâ room, ease the door open, and tiptoe over to the bed to make sure they were still breathing.

The more we know about the world, the more there is to fear. I wish we talked about it more, but it seems that fear is the final taboo. We like to think we should be over our fears by adulthood â that we should be better, more perfect, more evolved. The opposite is true for me, and Iâm convinced Iâm not alone.

In my opinion, most adults carry around deep, sloshing cisterns of confusion, pain and fear. We move slowly and carefully, lest we spill a drop and expose ourselves. Our fears are among the few things that unite us, yet we suffer them quietly and alone.

âAs far back as I can remember, every minute of life has been an emergency in which I was paralyzed with fear,â writes poet and essayist Mary Ruefle in Madness, Rack, and Honey.

Yet why is it that all we hear are stories about people who overcame their fears? Of public speaking. Of snakes. Of air travel. Of failure. Even of death. We celebrate these achievements. We talk about âconqueringâ our fears as if they are a cancer â and as if there were a cure.

Until recently, all that talk of fear-squashing sounded pretty good to me. At 38, I still have much in common with the child edging toward the panic button. Many nights, I close my eyes and wonder whether this will be it. I live in Oakland, California, so my specific and immediate concern is whether tonight will be the night my apartment building will collapse on top of me. The Hayward Fault runs less than three miles from my home and is notoriously overdue for âThe Big One.â

With the recent string of earthquakes in Southern California, itâs become even easier to imagine myself buried under rubble, suffocating, my back broken, unable to call for help. In other, more optimistic scenarios, I emerge from the building into the fresh hellscape of my neighborhood, bleeding and starting to walk toward the hospital.

When I drive across the bridge to San Francisco I am frequently seized by fear. Rather than admire the view, I think about an earthquake buckling the concrete and ripping the steel girders in two, sending my car straight to the bottom of the bay. I try to strategize: Should I bail out of the car while itâs falling? How long would I survive once the car hit the water?

Itâs not just earthquakes that keep me up at night. I canât stop thinking about all the potential ways catastrophic climate change will end life as we know it. But I may not be around long enough to witness that . . . because I also semiregularly convince myself I have a new terminal health condition. I wake up after a night of Googling and my search history is still open: âEarly Stage Ovarian Cancer â Three Signs to Look Out For.â âWhen to Get Tested for Alzheimerâs.â

I am a treat at parties.

Just kidding â I donât tell anyone I have these thoughts.

Whatâs worse, my thoughts no longer just poison my mind. Iâve started clenching my jaw in my sleep and had to get a tooth repaired. And this spring, I experienced my first panic attack in 15 years. It was such a nonsequitur that I didnât even understand what was happening until later. One moment it was a beautiful Saturday, the next I was crumpled over on a bus-stop bench, nauseated, breathless and confused. How odd, I remember thinking. Why canât I make this stop?

When I have a problem, I usually poll my friends. So I put a message on Facebook, asking them to volunteer some stories about their fears. Implicit in my asking was a hope that they would also tell me how they overcame them. Something I could pilfer and apply to my own life.

Clearly, I didnât understand fear.

One of the people I talked to for this story â weâll call her Morgan â had a terrible fear of heights. She would go to theme parks with her friends and watch people screaming with joy on the roller coasters, knowing how ill it would make her feel to climb up and strap herself in. Sheâd force herself to do it anyway. One day, when she was 19, it dawned on her that she could conquer her fear â and impress her motorcycle-loving boyfriend â by learning to fly propeller planes. She found a flying school at a local airport and signed up for 10 lessons on the spot.

âI set out to prove to myself that I could do something that scared the living shit out of me,â she says. âIt was stupid and bizarre and harsh.â

Flying was more satisfying than sheâd projected. With her instructor beside her in the cockpit, Morgan could force her attention onto the intellectual aspects of gauges and weather and how everything worked. She learned swiftly and built confidence. When her lessons were complete, she even let her instructor persuade her to fly solo. Morgan felt certain sheâd be cured.

The day of her solo flight, Morgan tried to stay calm by telling herself the plane was just a machine â a car you drive in the sky. Taking off, she felt the fuselage give a tiny shudder and then she was airborne.

It was magic. She felt like Amelia Earhart. She was the one who had pulled that piece of metal off the ground and was circling in the sky.

Then she realized that she had to land. She tried to squeeze down her mounting panic by recalling her training. Rather than let herself think about crashing, she checked off every step, one by one. In the end, she made a perfect landing.

But Morgan was disinclined to celebrate. The moment she cut the engine, she knew she would never fly a plane again. Her fear of heights had returned in full force. Four decades later, she has come to accept that it will never go away.

People spend their days quietly coping with fear. âWhen an elevator goes up, my palms start to sweat. I canât control it. I know itâs totally irrational,â says one man I know who developed some new fears in midlife but doesnât tell people about them. Letâs call him Roger. He says going above the 20th floor is guaranteed to induce a panic attack.

Roger lives in a town with mercifully few high-rises. When he travels, he always requests a hotel room as low to the ground as possible. He also hates flying. He would rather drive eight hours than take a one-hour flight. He doesnât know how these fears got started; they just happened. Today he copes with Xanax.

Another friend â Iâll call her Claire â traces her fear of heights to a trip to Italy she took three years ago. She was driving up a winding mountain road toward a cliff town to take in the view. After a lifetime of happily climbing to the tops of European castles, standing at the stomach-churning edges of canyons and exploring Californiaâs mountains by car, something changed. The road was practically cantilevered over the sea. Every time she hit another switchback, it felt like she was about to tip over the edge.

Soon after that, she started to suffer panic attacks on mountain roads. Her palms and feet got clammy and she worried that she wouldnât be able to hold on to the wheel or hit the brakes in time to save herself.

Then the claustrophobia set in. A year later, while hosting a party at her house, Claire accidentally locked herself in her bathroom. She had to remove the handle and jimmy open the door. She started avoiding bathrooms at cafĂ©s, especially the ones with heavy deadbolts. On airplanes she asks a flight attendant to please watch the door â she canât bear to lock it.

Claire went to a psychologist who prescribed exposure therapy to help her fight her fears. No way was that going to happen, she says, so she, too, uses antianxiety medications. âIâm not over the anxieties, but my response to them is much more muted,â she explains. âAs a woman, especially, I donât want to lose my independence because of fear.â

I started out writing about âhow we come to fear,â but I actually think itâs more accurate to say that our fears come to us. And if we canât forestall them, what hope do we have for resisting their influence?

Security expert Gavin de Becker says thatâs the wrong question. His book, The Gift of Fear â published in 1997 and still the most popular fear-advice book in a crowded marketplace â argues that fear plays an innate role in keeping us alive. In his professional experience helping people assess threats from co-workers, ex-partners and stalkers, de Becker believes tahat when it comes to predicting violent behavior in particular, fear sends us helpful survival signals that we too often choose to ignore. Instead, we should embrace the fear as a kind of intuition, a guide to predicting that something bad will happen.

But hereâs the catch: The helpful kind of fear, he says, is short-lived and rare. And it really only helps us avoid unexpected dangers like an assault, not the things some of us have feared for years, like earthquakes or heights or being trapped in enclosed spaces.

âReal fear is a signal intended to be very brief, a mere servant of intuition,â he writes. âBut though few would argue [with the notion] that extended, unanswered fear is destructive, millions choose to live there.â

De Becker distinguishes between useful fear (which manifests when weâre threatened) and useless fear. He points out that in a life-threatening crisis, fear is often the last thing we feel. Claire can attest to this. She has been held up at gunpoint, and sheâs been in car accidents. She stays calm and enters a state she calls âtaking-care-of-business mode.â Iâve had similar experiences after car accidents. The terrible thing has happened. You accept it immediately and launch into problem-solving. Fear is absent.

âThe very fact that you fear something is solid evidence that it is not happening,â de Becker notes in a neat turn of phrase. âIf it does happen, we stop fearing it and start to respond to it.â

So, whatâs happening to me when I startle awake at night, trembling, my heart pounding so hard that I mistake the sensation for my bed shaking in an earthquake?

According to de Becker, thatâs not authentic fear. Itâs worry. âWorry is the fear we manufacture,â he says.

When I read those lines, I frowned at the word âmanufacture.â I doubt the people I interviewed would say theyâve manufactured the burden of their fears.

But de Becker insists that remaining in a state of fear â like a car alarm that wonât shut off â is a choice, and it is more dangerous than we think, because it often leads to panic. It could even cause more harm than the fear itself.

Too bad fear and worry feel the exact same way in our bodies â like an existential threat.

This makes perfect sense on a physiological level, says journalist Jaimal Yogis, author of The Fear Project. That shot of cortisol that makes me gasp at night is a symptom of the classic fight-or-flight response that Harvard physiologist Walter Cannon first characterized in 1915. Weâve all experienced the rest of them: dilated pupils, tensed muscles, elevated heart rate.

These symptoms are governed by the amygdala, which has been protecting us since early hominids faced down saber-toothed cats and giant hyenas. Unfortunately, our amygdalas have not evolved with the times. I can set mine off reading a scary headline on my smartphone.

âBy the time you can say âIâm afraid,â your body is already well into the stress process,â Yogis writes. We have no medium setting built into our bodies for medium-sized scares. Itâs just an on/off switch. Thereâs no going back once youâve hit the panic button.

Over time, chronic anxiety can translate into devastating physical disorders like pulmonary disease and cardiovascular problems. It can disrupt the central nervous and endocrine systems, flooding the body with stress hormones like cortisol, which in turn contribute to all manner of issues with sleep, weight gain, diabetes and, yes, even teeth-clenching at night.

What of this idea, then, that we can choose a better way? De Becker offers three behavioral tips that underpin his philosophy of grappling with dreaded outcomes.

1) When you feel fear, listen.

2) When you donât feel fear, donât manufacture it.

3) If you feel yourself creating worry, explore and discover why.

âWorry will almost always buckle under a vigorous interrogation,â he writes triumphantly, and you can almost see the sheriffâs badge gleaming on his chest.

But the problem with all our fears is that they tell good stories. The plots may vary, but the core message is unsettling. Itâs about uncertainty, about our profound lack of control over our lives, on this planet, in this universe. Objectively speaking, potential disasters are everywhere â epidemics, asteroids, drunk drivers. They could strike us down at any time. Our nervous systems keep us aroused, sniffing the air for the next threat. And when you see it that way, it makes sense to stay vigilant for all of them.

âAnxiety, unlike real fear, is always caused by uncertainty,â says de Becker. When we canât predict something, we canât prepare for it. Weâre forced to admit thereâs nothing we can do. Welcome to the human condition.

Sometimes, our fears also depend greatly on context. The Chapman University Survey of American Fears offers a fascinating snapshot of just how much our fears and anxieties can change over time based on the media zeitgeist â and which ones abide, year after year.

In 2016, for instance, three of the 10 most prominent fears Americans cited were terrorism, gun control and Obamacare â all major themes of the presidential campaign.

In 2017, according to the survey, Americans widely feared getting into a nuclear confrontation with North Korea â at a time when the Trump administrationâs nuclear brinkmanship and âfire and furyâ threats were constantly in the news.

In 2018, for the first time, five of the top 10 fears were about destruction of our environment: contaminated drinking water; the pollution of oceans, lakes and rivers; bad air; the mass extinction of flora and fauna; and global warming. At least now I know I have company.

What I find most interesting, however, are the three universal fears that climb to the top of the chart every year and sit there, unmoving, like Danteâs shrieking harpies perched in the tortured wood. Two are closely connected: the twin fears of a loved one becoming seriously ill and of a loved one dying.

The third is the consistent number one thing we Americans fear: the behavior of corrupt government officials. Regardless of party affiliation, it seems people most fear government malfeasance.

That may seem odd, but to the worrier, all fears have their own logic. Mine are no exception. The Hayward Fault will definitely erupt . . . sometime. The climate crisis is here, and itâs going to get worse. And everyone dies of something, whether itâs cancer or a wrong turn off a steep mountain road.

How are we supposed to handle ourselves in the meantime? This is as much a question about living, Iâve come to realize, as it is about coping with lifeâs less appealing features: uncertainty and lack of control.

For me, catastrophizing â thinking about the worst possible thing that could happen and letting my mind deal with the consequences â offers a kind of perverse comfort, the promise of tussling with my fears and shoring up my resilience to suffering. The trouble is, I never actually escape the fear loop. Iâm never really reassured. And this minute-by-minute, hour-by-hour anxiety drip becomes its own eternal wellspring. Anyone who has a history of panic attacks will tell you that the fear of having one can be enough to set the next one off.

âIn terms of fear of heights or flying, what I actually fear is the feeling of panic, of being trapped and unable to get away, and how Iâll act and feel. Not so much crashing. So that you begin to fear the fear,â says Roger, the man who avoids flights and elevators. Fear will just metabolize itself after a while.

I sometimes think about my young self and wonder what happened to me. Why wasnât I more resilient? Did my parents not cultivate my independence? Iâve started wondering about how much our early development and even our personalities shape our viewpoint when it comes to risk and fear. When I was 11 and facing a night alone, I perceived those parentless hours as a harrowing ordeal. But some other kid might have turned them into an escapade, watching off-limits TV channels and gorging on junk food all night.

I am acquainted with people who go through life assuming that everything will be OK. And even when it wonât, they see no point in worrying about it, because thereâs nothing they can do to prevent bad things from happening. My grandmother, for instance, had a favorite expression: âWhat is, is.â She held tight to those words amid several life-changing setbacks, and lived to age 96. I envied her disposition, but I will never be like her. My version of resilience involves planning for the worst, even though I know itâs an endless iteration.

So Iâve been looking for a third way â a middle path. When someone recommended I read The Places That Scare You, a book of Tibetan Buddhist teachings by Pema Chödrön, I resisted at first, even though I have my own flailing meditation practice. I worried that she would tell me that fear is an illusion or something equally trite.

But unlike Gavin de Becker, Chödrön doesnât claim we can ditch our long-term fears. She says theyâre part of the human condition. Chödrön describes fear as something we learn early and often â itâs a product of circumstances that âharden usâ until we become resentful and afraid, she says.

We can ease fearâs grip by opening ourselves up, over time, to what hides beneath: tenderness and vulnerability. She says these two qualities could take us a lot further in life, but most of us have bricked them off and poured concrete over the wall for good measure.

âTapping into that shaky and tender place has a transformative effect,â she writes. âBeing compassionate enough to accommodate our own fears takes courage, of course, and it definitely feels counterintuitive. But itâs what we need to do.â

Rather than waiting for our fears to overtake us on their schedule, she suggests we acknowledge their shrieks and look up at the branches where they perch in our lives every day. That we get to know them.

Weâd rather do almost anything else. I know I would. I would rather numb myself watching YouTube far into the early morning hours than spend another night facing whichever fear asserts itself.

Chödrön says that tendency only makes things worse. âOpenness doesnât come from resisting our fears but in getting to know them well,â she writes.

I am trying. Sometimes when Iâm fearful now, I let myself acknowledge how it feels â Iâm scared. This is scary.

Other times, I try to bring some of my reporterâs persona to the moment and become curious â an approach Chödrön mentions in the book. Asking âWhatâs really happening here?â and âWhatâs under this feeling of panic?â can yield results. Itâs possible my presumption that I have a terminal disease has something to do with my deeper fear of failing at life, of not having mattered at all. Maybe my horror of earthquakes is tied to a distasteful reality Iâd rather avoid: the impermanence of this life Iâve built, and having it taken away from me.

I no longer shake my head at that little girl who sat on the edge of her parentsâ bed, sweating in too-much clothing, eyeing the panic button. She had a certain wisdom. Deep down, she sensed a truth her parents couldnât refute: Life is uncertain and few things are within our control.

Fear seemed like the best way to handle that news at the time. Iâm hoping itâs not too late to learn another way.

I also regularly give in to â and Iâm not sure Chödrön would approve of this â the exigencies my fears demand. Last year, I purchased two heavy, fully stocked earthquake-emergency backpacks. I stashed them in my car and my apartment. I bought two more for my parents for Christmas. (They were confused.) I also treated myself to a shiny new fire extinguisher, even though my old one was not expired.

The friends I talked to all choose to be out in the world despite their fears. But their lifestyles are limited, and the doâs and donâts are a process to be managed, constantly. Claire still likes to explore steep mountain roads, but only those with a barrier. She feels sick when sheâs obliged to drive over a long bridge, but she can handle it if someone else, like a bus driver, is at the wheel.

Morgan attributes her fear of heights to a childhood wound that never healed. Some things she simply wonât do, like roller coasters and downhill skiing. But sheâll climb a mountain for the beauty. Itâs hard to do â sometimes really hard â but thereâs simply no other way to enjoy the vista. When I asked her how she overcomes her fear, she gently corrected me.

âI have found of myself that a surrender practice is the best. Itâs not a conquering, or a getting over, or a getting away from,â she said. âAnd climbing a mountain is another form of that surrender practice.â

We can keep ducking our fears, but at a certain point they prevent us from seeing the view. I could leave Oakland, but I love my tranquil apartment, my neighborhood, the white-blossom magnolia tree in the courtyard, and the patio where I can contemplate its flowering while I meditate. So I choose this.

âWhat has life taught me? I am much less afraid than I ever was in my youth â of everything. That is a fact. At the same time, I feel more afraid than ever. And the two, I can assure you, are not opposed but inextricably linked,â writes Mary Ruefle.

Bad things will happen. To me and to the people I love. To the planet, and the creatures on it that donât have a voice. I know this to be true. But something good could happen, too: the type of alternative ending my mother tried to teach me to construct. With all my planning and preparing for the worst, I have little space to imagine an actual future. The version of the story in which I go on living â not because of my fears, but despite them.

Tags: Chapman University Survey of American Fears, climate crisis, Fear, Gavin de Becker, Julia Scott, Mary Ruefle, Notre Dame Magazine, Pema Chodron, The Gift of Fear, uncertainty

Posted in Feature | No Comments »

The Enchanting Mr. Rice Guy

Thursday, January 20th, 2022

Hereâs the last time I remember playing with my childhood imaginary friend, Mister Rice Guy. Iâm 8, and itâs my least favorite time of day: recess. Iâm friendless and alone at my new school, and so I bring him with me that day â normally he stays home. We walk the perimeter of the chain-link enclosed yard behind the school as kids around us scream and play. My classmates assume Iâm talking to myself, so they start mouthing my words, wreathing them with derisive laughter.

Until that day, my imaginary friend had been a source of comfort. That moment transformed him into a source of shame. Mister Rice Guy (whose name I am sure I took from misunderstanding the phrase âMister Nice Guyâ) disappeared.

Thirty-two years later, in the nadir of a global pandemic, he came back again. But more on that in a moment.

According to my parents, Mister Rice Guy first showed up when I was 5. I was an awkward only child with a need for an imaginary companion who understood me. I was very private about him. He never came to the dinner table, and I never told my parents what he looked like. He and I spent long hours locked in conversation, playing together on the floor of my green-carpeted bedroom. What did he look like? In later years, Iâve been embarrassed to admit I couldnât quite remember. What I do know is how he made me feel. Safe and warm. Seen, heard and protected.

Maybe you had a special friend in childhood who made you feel that way. Or more than one. The experience exists on a spectrum, stretching from conversations with a favorite toy or stuffed animal to personified imaginary entities like mine.

For the most part, children know these friends are âpretend.â Thatâs the point. Theyâre not a delusion, but rather a way to access feelings and qualities that our youthful selves know to be important, but which weâre not ready to claim as part of our essential identities. Theyâre our emotional backpacks, apart but close at hand, there when needed to deliver a store of strength or calm.

Experts say a childâs imaginary friend can be someone to consult when making a decision. They can make us feel better about our peer relationships, giving us insights on how to handle friendships and disagreements. And they offer the capacity to imagine new outcomes to difficult situations. Feeling trapped and confused, say, in a pandemic? Your imaginary friend might help you imagine a way out.

âThe kind of mind that can reason about the past and think about the future is the kind of mind that can come up with an alternative,â says Marjorie Taylor, a professor emerita of psychology at the University of Oregon. Taylor has studied childrenâs fantasy lives for decades. I called her up recently to ask if I was crazy, because suddenly Mister Rice Guy was back.

No, she said. I was not crazy. In fact, more adults could benefit from finding new ways to play.

In the shortest, darkest days of that first fearful winter, as COVID-19 mutations circled the globe, I sat at home, hushed and frightened and uncertain. From bleary days to long, insomniac nights, a heaviness assailed me in my solar plexus. It dragged me down and made me cry, on and off, for days at a time. And then suddenly, one night, all I could think of was Mister Rice Guy. I swore I could feel his presence in my bedroom.

Was I losing my mind? I looked around in the dark and felt like a fool. Why would my old companion be back in my life? Could he even recognize this sad, 40-year-old variation on the (also kind of sad) child he had comforted at the age of 8?

The next morning, I woke up, exhausted and confused, and took a hike for the first time in months. I drove to a hilly park with fresh green grass. At the outset, I wondered if Mister Rice Guy would tag along, but still it made no sense. Why would my old companion want a friend like me? I was weepy and depressed and old. If he were there, heâd want to play.

Suddenly I knew what I needed to do. I took off my pack, climbed a medium-size hill, waited until no one else was looking â and rolled down that hill. I collapsed at the bottom, giggly and dizzy and covered in burs. You cannot be sad after you roll down a hill. And I know for a fact that I didnât roll down that hill all by myself. I got a push from Mister Rice Guy.

After that, we spent a lot of time together. As the first pandemic winter yielded to its second spring, I left my apartment as often as I could, taking long walks where I paid special attention to bird and insect worlds. What were their days like? I imagined walking side by side with Mister Rice Guy on these explorations, which made them feel adventurous and fun. That line of ants streaming by a smeared banana â where was their nest? (We tried to follow the trail of ants for as far as we could.) How closely could we sneak up next to the hummingbirds on my street before they zoomed away? By then Iâd realized, to my delight, that I hadnât forgotten what my childhood friend looked like: He looked like no one, or like everyone who isnât me. In an era that seems all too ready to demonize the Other, here was a presence of pure Otherness, radiating the acceptance I hadnât been able to access on my own.

If someone saw me talking to myself, let them wonder. I felt no shame.

Iâm sure I am not alone in having invoked a childhood presence for my own comfort over the past year. More than one friend has told me they reached for their oldest, most cherished stuffed animal in recent times â rescuing them from closets or shelves, gently stroking their much-repaired coat and reconnecting with ancient feelings of safety and innocence.

I spent 32 years living without Mister Rice Guy, because I made friends and gained confidence out in the world. But I had forgotten how to play.

Weâve all observed the intense absorption of children at play. As a writer, Iâm envious of their ability to invent characters, storylines and games without effort. Imagination is a form of pleasure and escape. Itâs not quite like an adult daydream. To play is to live in the present, unremittingly, without distraction or self-judgment. Thereâs a sense of discovery and wonder.

Playfulness is a collective trait. âI can walk into any daycare anywhere in this country and see children pretending all day long,â says Taylor, who wrote the definitive book on pretend friends and has spent her career unraveling the mysteries of why we play. She believes the instinct for imaginary play is universal, and that imagination itself is fundamental to the human condition. And not just for humans. Taylor points to a handful of studies going back to the 1950s that suggest gorillas, chimpanzees and dolphins engage in imaginary play â among each other or with their human interlocutors.

The âwhyâ of it is less evident: Play may serve a profound evolutionary purpose that we still donât understand. But the capacity for imagination benefits us all our lives â whether itâs to propel us to the moon or to write the occasional poem. We also all have the capacity to think about things that donât exist, might have been or could be. Thinking about the past, imagining a future: These are the tools of fiction. And what is our daily self-talk if not the adult version of our childhood attempts to cope with these past and future notions?

Who can we be speaking to?

Imaginary friendships werenât even thought to be good for children until the 1990s, when an efflorescence of research began to suggest otherwise. Today, having fantasies of this nature is considered not just healthy, but an important rite of passage for some. Studies by Taylor and others suggest that up to 65 percent of us had an imaginary friend, or multiple friends, in childhood or adolescence. (Other studies suggest the number is much lower, around 30 percent).

Researchers have found that the presence of an imaginary friend â whether a wholly-invented figment of a childâs imagination or a favorite object like a stuffed animal that has a personality and âconversesâ with the child â tends to correlate with high levels of creativity and empathy. Some of us invented entire worlds with imaginary characters and storylines, called paracosms. In doing so, we gained a whole lot more than companionship.

The benefits also accrue later in life. Several recent studies have shown the experience of having an imaginary companion likely makes adolescents and adults more independent, resilient and prone to ask for help when they need it. And, yes, adults who used to have imaginary friends do engage in more self-talk than other people.

But why might I â or any of us â seek a reunion with our pretend playmates? The answer may lie in the disorienting circumstances of our new reality. My childhood world was small and turbulent and vulnerable. Adults were the force majeure, compelling where I went and what I did. Our COVID-19 lives today are similarly proscribed, attenuated and disordered by forces outside our control. Thereâs a deadly pandemic on, and not even the grown-ups know whatâs going to happen next. Our worlds are again defined by hard boundaries and closed doors. And just like in childhood, we survey our lives in the lonely hours of before-sleep or before-dawn, waiting for the point where we again have something to look forward to.

For me, spending time with Mister Rice Guy helped me realize how big my world truly is, no matter how small it can feel inside the daily closed loop of my pandemic bubble. The last time he and I played together when I was 8, his world was bounded by my green-carpeted bedroom and the fenced-in recess yard behind my school. When he came back to me, we enjoyed a leisurely ramble through the Sonoma County hills all day, hunted for ripe blackberries and compared the personalities of the different cows we ran into (and tried to run up to) on skinny ranchland trails.

After we took those first post-vaccination forays into the world, my fears started to ebb, and Mister Rice Guy stopped coming around. Iâm OK with that â it was a reunion, after all, and this time his departure isnât the sudden banishment of an ashamed 8-year-old girl. Heâs gone away for now. But if living is coping with uncertainty, he could very well be back.

Heâll be welcome. I sleep better these days knowing I have an extra friend who requires no social distancing, who sees me clearly with his every-colored eyes. And whoâll remind me when itâs time to play.

Tags: childhood, COVID-19, Dr. Marjorie Taylor, Imaginary friends, Julia Scott, pandemic, Paracosms, The power of play

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on The Enchanting Mr. Rice Guy

Duolingo: Two Unexpected Entrepreneurs

Thursday, August 20th, 2020

EPISODE PART 1:

She Can Fix It

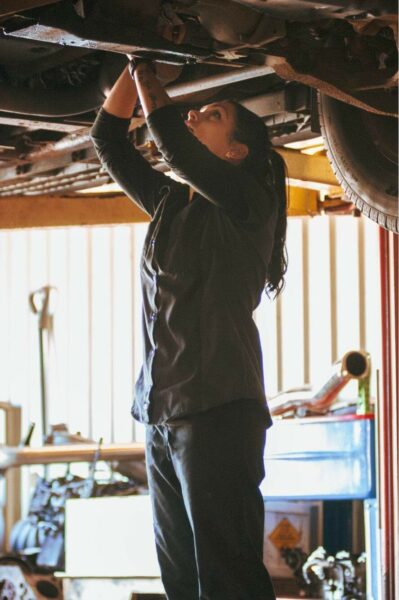

Stephanie Lopez is a woman in a manâs profession, something some men have never let her forget.

Stephanie, a mother of two, owns Woosters Garage in Weston, a small town in central Wisconsin. She named her garage after her great-great grandfather Glen Wooster, the first in a long family line of men â including her grandfather and father â who love fixing cars⊠a passion she inherited.

Today, Stephanie Lopez is proud to run her own garage. But her road there was bumpy, winding and full of unexpected barriers.

EPISODE PART 2:

Silicon Valleyâs Wizard of Jobs

Rahim Fazal seemed destined for a thriving career in the tech industry when the web company he co-founded as a teenager made him a millionaire overnight.

Rahim is 38 today. His dreams of making it in Silicon Valley eventually did come true⊠But along the way, he noticed that not everybody was equally welcome there. The troubling question of who gets to belong in the heart of the tech world â and who doesnât â eventually led Rahim to take the biggest leap of his career.

Tags: Duolingo, Entrepreneurs, inspiring, Joel Scott, Julia Scott, podcast, Rahim Fazal, Silicon Valley, Stephanie Lopez, SV Academy, Woosters Garage

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on Duolingo: Two Unexpected Entrepreneurs

On Being Alone

Tuesday, January 1st, 2019

When I was a little girl, I never dreamed of a husband or children. I never pictured a wedding starring me as the bride with white dress and elegant bouquet. I never pictured the groom. I couldnât see our first dance, the exotic honeymoon. No matter how hard I strained, I could not get excited about the issuance of babies with cute faces and soiled diapers.

Instead, I dreamed of a goat.

It could have been a sheep or a ram. Iâm not sure I knew the difference back then, or which image may have lingered in my mind after my mother finished reading me the stories of Heidi in the Swiss Alps and the Three Billy Goats Gruff. But at a certain age â the one where people start to ask you what you want to be when you grow up â the where seemed to be a lot clearer than the what. Whenever I pictured my adult life, I pictured a hillside high above a rural town. On that hillside, a small cabin where I would live. Next to that cabin, a goat.

As I learned about the world, and even began to travel a bit to Europe in my early teens, this vision became more specific. The cabin was situated on a hillside in France, in Provence, in a remote valley a short walk from a glittering view of the Mediterranean. I would get to know my neighbors and offer them tea when they passed by my open door. We would speak French together. I would write. Occasionally I would have a male caller, just one. The details of what we would do in the cabin were hazy. The male caller could come and go, but the main thing is that he knew when to go. The goat would be my main companion, and the source of delicious and nutritious milk, just like for Heidi. I would learn to love goat milk. I would relish my solitude.

It may not surprise you to learn that I was an only child. Growing up, this made me different from most of my classmates. They fought for their parentsâ attention and had to share a bedroom. I woke up alone. From early on, I had an imaginary friend named Mr. Rice Guy. I wish I could tell you I remember what I imagined he looked like. But I do remember how he made me feel. Being with him was safe and gentle. I think we must have spent endless hours together in my bedroom, on my frizzy green carpet, chattering and playing. Mostly I think I chattered and he listened.

When Mr. Rice Guy wasnât needed, I spent the bulk of my time inside books. But I also liked to do nothing at all â just look out the window at the alleyway behind my house, and daydream. I had friends over for sleepovers, which was fun because I owned all kinds of games, and you couldnât play Candy Land or Clue without someone else. But I was always a little glad when they left and I could sink back into the quiet of my room. I didnât have to share my stuffed animals. This was a perk, but it also meant that some of them went neglected, which I remedied by carrying a different one to bed with me on a rotating basis. I didnât want them to feel alone, although I rarely did.

Alone. That word seems like a threat, mostly. What do we do with children who misbehave? We send them to their room, alone. Tell them theyâre grounded, the punishment being to deprive them of companionship and force them to âthinkâ about what theyâve done. These days, we take away their electronics so they canât play games, go online or post updates on social media. The message: Time with others is a treat we earn. Being alone is a reprimand.

We find so much comfort in the presence of others, sometimes without realizing it. Even having someone in the next room is a comfort. But when the house is still and thereâs nothing else to do, the self confronts. And we would do almost anything to avoid hearing what it has to say.

What lives alongside solitude? Boredom, potentially. Anxiety, often. And the concept of loneliness has an overwhelmingly negative connotation â the absence of others is plain and uninspiring.

âIn a real dark night of the soul it is always three oâclock in the morning, day after day,â wrote F. Scott Fitzgerald. Fortunately, we have many tools at hand to prevent us from slipping into a 3 a.m. of the soul: theyâre our laptops, iPads, smartphones, books, magazines and TV remotes.

One of my favorite studies about the experience of solitude and loneliness â there is a whole subfield of social psychology devoted to it â took place in Atlanta in 2015. It surveyed 185 adults, aged 20 to 81, to determine their reactions to the experience of momentary solitude: those interstitial parts of the day when thereâs downtime with nothing to engage in.

The studyâs authors had the idea to analyze not just peopleâs stated feelings about solitude, but their physiological reactions to being alone. Specifically, they measured levels of cortisol â the âstress hormone,â activated when the body perceives a threat. Seven times a day for ten days, they had participants submit saliva samples â at random moments, when a beeper went off. Sometimes when the beeper went off they were alone, other times they were not.

Overall, cortisol levels were higher when people were alone, as opposed to being with others. Even if they said otherwise in the questionnaire, their bodies were stressed. But there were some interesting variations. People over 51 had a different response; their cortisol levels were lower. In fact, several studies have suggested that as we age, we mind our solitude less, and we may even prefer it â a neat trick as we approach a time of life where we may be facing more of it.

A review of the literature suggests that free will is the decisive factor here. Getting to choose solitude makes a big difference in how we handle it, and whether it contributes to our well-being. Yet there is a fragile line between the solitude that heals and the one that salts the wound. Many other studies have shown how involuntary solitude and isolation can prove not only anxiety-inducing, but dangerous â from a slightly higher risk of heart problems to deep-seated alienation, especially among vulnerable teens.

For me, a great deal has been lost of that little girl who knew how to be alone. Some writers (or future writers) crave a room of their own: I craved a life of my own. Served up in short, bracing doses, I discovered early on that isolation â the extreme version of solitude â can offer me the only hope I can ever have of knowing who I truly am and what I actually want, absent the âshouldsâ of the world.

But as an adult, even when I have it, Iâve become used to filling the silence rather than letting it speak to me.

I fall asleep and wake up next to my smartphone. The first thing I do, before I get up to go to the bathroom, is reach for the phone. I look at Google News and let algorithms tell me what to think and care about. I bite my nails without noticing. My habits have become more pronounced amid the ongoing national perma-emergency in our politics. The daily outrage drives the double-time news cycle â confronting me, all of us, every day.

Itâs not just my time thatâs being nibbled away by my devices, not to mention the whole superstructure of adulthood. Itâs my mind. Recently I noticed that I was having trouble generating original thoughts: problematic for a writer. I worry that, at 38, I have become a dullard. That my inner creative world has shrunk to the occasional glimpse from a carâs window while my smartphone chirps directions, always preventing me from exploring an intriguing side road or getting lost.

The impulse to create begins â often terribly and fearfully â in a tunnel of silence,â asserted Adrienne Rich. You can silence your cell phone. But the âfertilizingâ quality of silence, as she called it, wonât reach a distracted mind.

Even with all my electronics put away in a drawer, my apartment shouts at me from every corner. CLEAN ME OR YOU WONâT SLEEP WELL TONIGHT, says the carpet. READ ME, YOUR CAREER DEPENDS ON IT, screams my pile of unread magazines. Even with the sound turned off in the movie of our lives, thereâs always the directorâs commentary. See what happens when you glance at a bookshelf. Or notice the details of your childâs room.

When was the last time I was truly solitary? I couldnât conjure it. Iâm not talking about the default experience of solitude when weâre doing laundry, checking email or driving somewhere with the radio on. Some people harvest solitude for content (for instance, choosing to listen to a podcast) and others for insight (I include meditation here, because although it can be very helpful, it still has intentionality). None of these things are bad ideas â theyâre part of everyday life, mine included. But I wanted to explore around the margins, where the instinct to fill time loses its edge. My appetite for solitude may be greater than some othersâ, but in its ideal form, I donât seek to harvest it for anything.

Yet I am the first to admit that solitude â what I define as true solitude, the state of being alone without needing to do anything in particular â feels dangerous.

âSo afraid one is of loneliness, of seeing to the bottom of the vessel,â wrote Virginia Woolf, who saw the bottom of the vessel more than once. An overwhelming number of writers have detailed the contributions of solitude â and even loneliness â to the creative mind.

âWhat is needed is this, and this alone: solitude, great inner loneliness. Going into oneself and not meeting anyone for hours â that is what one must arrive at,â wrote Rainer Maria Rilke in 1903, offering advice to Franz Kappus, his tortured young protĂ©gĂ©. But even Rilke struggled to enforce his own solitude with the demands of family and the necessities of travel. And that was before YouTube.

I realized that I urgently needed to turn off the narrative channel of my daily life. So this summer, I made a little experiment. I would go away on a retreat, disconnect from everything familiar. I would rent a cabin in a part of California that was strange to me, and, to the greatest extent possible, be alone. I didnât want to go on a meditation retreat with a group of strangers. I wanted to unfurl, alone, without any fixed agenda. I wanted solitude, even if it was attended by troubling doses of boredom and loneliness. And the only way to do that was to remove myself from my âself.â Only then could I hope to access the deeper well of inner silence â true isolation â and explore what it had to offer.

The term âsolitude,â though, continued to bother me because it didnât quite describe what I was missing. A friend of mine came up with the concept of self-visitation: the active work of peeling away those aspects of life that distract one from oneself. It is conscious, methodical subtraction, without any expectation of a payoff or reward. True self-visitation contains no epiphanies; it is simply the communing familiarity of self in space and time.

But with the layers stripped away and no one to step in and tell me how to think or who to be, what version of myself would I be left with? And, whispered a voice I was ignoring, what if she doesnât have anything interesting left to say?

Looking online, I found a one-room cabin up north in a town Iâd never heard of, Forestville. It had no electricity, no Wi-Fi and no indoor plumbing. There was an outhouse and an outdoor sink and shower. Meals could be wrangled on a butane burner. Trying not to think too hard, I booked it for three nights.

As I made ready to leave, I made some other decisions. My phone could come with me in case of emergencies, but would be turned off and locked in the glove compartment of my car. No laptop. No alcohol, no caffeine. No music. And no books â I would need to leave my books at home. The only companion for my mind would be a journal to write in. Not with any writing goal in mind, just to record my thoughts if I wanted to.

âBut wonât your mind start to spin when youâre alone?â asked a friend. I shook my head, but I didnât really know. I would deal with the dark night of the soul if it came to pass, at 3 a.m. if need be.

Another friend looked at me in horror when I told him I wouldnât be bringing along any reading material. âNot even one book? Canât you hide one under your floorboard, like a box of crackers in case of emergency?â

I waited until the last minute to pack for my retreat, cramming the morning full of work deadlines. Itâs a simple hour and a half to Forestville from where I live in the Bay Area, but I arrived three and a half hours later than expected. I was still checking my phone and answering emails up to the moment I pulled up on a Monday afternoon. My host, the owner of the property, was there to greet me. To get to the cabin, he helped me carry my bags down a long wooded lane, over a soundless creek tamed by the heat. The only other house on the property belonged to him, and I couldnât see it through the trees once I settled in.

It was even smaller than advertised â just a bed, desk and chair, a side table and a narrow armoire, stuffed with linens. The outhouse was 100 feet away, which I suspected would be interesting at night. No goat, alas.

Looking around, I thought of Henry David Thoreauâs description of looking at his simple cabin, his pond, his woods and his bean field. âI have, as it were, my own sun and moon and stars, and a little world all to myself,â he wrote.

The first thing I did was to take down the heavy mirror behind the bed, which trailed a skein of absconded spiderwebs as it left the wall. I put it on the floor, facing inward. I didnât want to witness myself witnessing myself. I carefully washed my produce â two apples and two tomatoes â in the outdoor sink that, I discovered, drained straight to the forest floor. I brought them inside and lined them up on a windowsill with my two lemons in a little pattern. There.

I fetched a pot to make hard-boiled eggs over the butane burner and it had two living spiders in it, one of which did not want to leave the pot and merely surfed the water. Suddenly, I felt a sharp sting on my lower back â and immediately decided I had been bitten by a tick carrying Lyme disease, my superparanoia. (It turned out I had no bug bite at all.) I had a brief, panicky moment when a bee buzzed past my ear and the sound made me think I had missed a text on my cell phone. Actual panic â my heart was pounding when I remembered my phone was turned off, in my car.

In brief, I was nearly insensate of the pleasures of my new home that night. I could tell it wouldnât be a silent retreat. I could be as quiet as I wanted, but I was staying in someoneâs rural backyard. I lay on my back far into the night and listened to trucks buzzing by on the main road and a demented dog barking in the distance. Absent other distractions, my mind immediately started to cannibalize what I had last fed it, devouring the finer plot points of Sherlock and replaying the opening bars of Satieâs GymnopĂ©die No. 1 over and over again. Then I started to catalogue all the ways in which I had caused friends or family members to feel neglected, hurt or let down over the years.

The next morning was so bright and cloudless that when a hawk passed for a moment above where I sat with my journal and morning tea, I wondered whoâd turned out the lights. I claimed a wobbly bistro table with peeling green paint on the narrow deck outside my cabin. Twice a day I brushed away the leavings from the redwoods and coast live oaks that hung over the deck. The oaks shed their leaves constantly. I could hear them ding onto the metal roof as I lay in bed.

I walked the property, then took in my private fire pit. It sat in a clearing with six brightly colored Adirondack chairs around it, clearly awaiting the company of friends. I watched some dusty salamanders sun themselves on the circle of rocks and dart across the ash, and wondered if I would make myself a fire, and whether it would be sad to sit in one of those jolly chairs and stare at the flame, alone.

What on earth would I find to fill my days with, my friends wanted to know. It seemed like a strange enough question to me as I sat at my green table, long enough to watch the transit of the sun to what must have been high noon, judging by the heat. I watched two skittering brown squirrels chase back and forth between a pair of elegant oaks on opposite sides of the laneway. The trees had grown toward each other until their branches crossed like broadswords.

In the woods, what you notice fills you to the brim. I could have sat far longer, but there always seemed to be something to do â although nothing that needed doing beyond basic survival. Of course, there was the meal prep and cleanup, the daily troubleshooting â What substitutes for a colander? â the dressing and undressing and showering. The journaling was optional. (I suppose the showering was, too, but Iâm not an animal.)

I took strenuous hikes on the Sonoma coast. It transpired that there were many important things to do: to pause, overheated, every few hundred yards on an uphill climb and notice, as I tried to catch my breath, how the spines of sword ferns have a soft coating that belies the brittleness of the leaves. I paused to taste wild blackberries and savor their tartness; to meditate by a creek, and caress the moss next to my feet; to pick a clover from the mounds that grew up around the redwood fairy circles, and chew the stem to enjoy their secret lemon flavor; to observe how the sun filtered through the ferns, stenciling the roseate soil with a living photo negative.

I noticed and did things without noticing or doing things, just because I was curious and it felt good. It turned out that I liked my mind after all.

âThe greatest thing in the world is to know how to belong to oneself,â wrote Michel de Montaigne around 1572. When I was on forest time, the world belonged to me. I stopped feeling anxious. The most significant questions pertained to the timing of dinner and bedtime. I learned to gauge how much daylight remained by eyeing the corona of blue in the sky above my cabin clearing, rather than the crepuscular creep along the forest floor. Still I misjudged a couple of times and ended up brushing my teeth and showering after dark, with a flashlight, having a giggle at my own expense.

I wrote without effort, often at night in bed with my journal propped up on my knees, straining with a candle in one hand and a pen in the other. On my last evening, I built a fire and sat next to it, eating my meal. I looked around at the five other empty chairs and did not feel any desire to fill them. âThis is as close as I come to feeling holy,â I wrote that night.

But I hadnât thought about what would come next. Within 45 minutes of leaving Forestville the next day, I had bitten off two nails and was taking mental notes of all the things I needed to accomplish as I zoomed down Highway 101. I had a long and guilty reunion with my laptop that afternoon.

My reentry was wobbly. As easily as I had settled into my solitude, I felt myself losing the thread. I cried a lot. I had trouble sleeping, trouble working. For a time, I stayed off Google News. In the car, I forced myself to sit in silence and avoid listening to the radio. I meditated in the morning. I lit candles at night. But little by little, I felt my old condition settle in somewhere near my solar plexus: that state of dullness mixed with hypervigilance.

The world felt immense and harmonious when I spent my days hiking in vast places and sleeping in a very small one. But now, with access to everything in the world on my computer, in the Bay Area, and at the supermarket, it felt like I had fewer choices. The air in my lungs felt compressed. I didnât experience the same sense of possibility.

I had been hoping to portage some elements of my retreat life into my ârealâ life, but I forgot that the same person â me â is always there, struggling and striving and kicking and generally making a mockery of attempts to honor my goals and stay aligned. I should have read my Montaigne more closely: âAmbition, avarice, irresolution, fear, and lust do not leave us when we change our country. . . . Neither deserts, nor rocky caves, nor hair shirts, nor fastings will free us of them,â he wrote.

It took only three days of self-visitation to remind me that my internal compass still points in the direction of true north, just as it did when I was a child. But how do I keep it in my sights when Iâm getting spun in circles? And, when I find it again, how can I follow it without walking out on my life, when there are so many things that deserve my attention â a project thatâs due, a friend whoâs in pain, this countryâs civil rights, our environment?

How can I live in the world, engaged and open-hearted, while cultivating my inner silence and need to withdraw?

Montaigne thought it might be possible to do both. âReal solitude,â he wrote, âmay be enjoyed in the midst of cities and the courts of kings; but it is enjoyed more handily alone.â Thoreau returned to society after two years, and when he was at Walden he had frequent visitors â he describes his small cabin filled with up to 30 people at a time. He was no hermit, but walked frequently to town along the railroad tracks and recounts his conversations with all manner of folk who knew the woods.

There is something reassuring about these questions, and the fact that they have been with thoughtful writers for such a long time â Friedrich Nietzsche, Thomas Merton, Annie Dillard, May Sarton, Emily Dickinson, Louise Bogan and hundreds more. They all sought a balance between the version of themselves they gave to the world, with its traumas and distractions, and the need to belong to themselves, cultivate their autonomy and create something original and true. They werenât just talking about how to write, but self-visitation in the everyday.

My childhood vision has come true. I never did marry or have children, and I have yet to even cohabitate with anyone, although I have had several meaningful relationships. I donât own a hut on a hillside, but I do have a male caller. He, like me, relishes his solitude and knows how to respect mine. I intend to take a self-visitation retreat every year. In the meantime, I will do my best to keep my door open and, after all the visitors leave, get back to the page, alone.

Tags: essay, Henry David Thoreau, Julia Scott, loneliness, Michel de Montaigne, Notre Dame Magazine, solitude, Virginia Woolf

Posted in Front Page | No Comments »

How Canadians Took Silicon Valley… And Never Owned the Win

Tuesday, June 12th, 2018

[Original story here: https://thelogic.co/news/the-big-read/origin-story-canadians-in-silicon-valley/]

Lars Leckie knew C100 had arrived when he was walking down the street in downtown Toronto a few years ago, crossing an intersection while wearing his C100 jacket. A young entrepreneur stopped him mid-stride, and introduced himself. ââItâs so great to meet someone from the C100!ââ Leckie recounts the man telling him. âAnd Iâm like, âIâm just in downtown Toronto, Iâm not at an office where you expect to see startups,ââ says Leckie. âIt was pretty cool.”

Bay Area venture capitalists like Leckie, managing director at Hummer Winblad Venture Partners, rarely get that kind of open-mouthed rock-star treatment in Silicon Valley, although they are a key part of its mystiqueâthe golden-robed men and women who, like ancient Roman emperors in the Colosseum, control pollice verso the fate of companies and the circulation of economy-altering sums of money.

But together, the charter members of C100 have inspired their own mystique, a coveted stamp of approval. C100 is a small, member-driven non-profit that connects Canadian tech entrepreneurs with the Valleyâs top Canadians in the industry. Hundreds of companies apply for 48 Hours in the Valley, its signature program, each year. Only 20 are selected. The pitch session trainings and mentorship that CEOs receiveânot to mention introductions to fundersâhave contributed to the growth of companies like Clearbanc, Frank And Oak, Kik, Wealthsimple, Tulip and Well.ca.

All told, more than $3 billion in venture capital was invested in Canada in 2017, and another $3.2 billion the year before that. C100 estimates that the funds companies with a C100 connection since 2010 easily stretches into the billions. Yet the story of Canadian excellence in the Valley is fraughtâand not just by conversations at home about âbrain drain,â even as Canadian entrepreneurs continue to derive a net benefit from the training they get from U.S. universities and tech jobs. The other issue is the hidden history of Canadian success itself.

In its reluctance to acknowledge the realities of the modern tech diaspora, Canadiansâor the Canadian press, at any rateâhave inadvertently overlooked the names and diminished the achievements of generations of Canadians who handed the baton to the tech workers transforming our digital economy.

The resulting lacuna may seem benign, but it has had real consequences for todayâs tech talent, according to Canadians I spoke to in the Valley. Itâs fostered a hesitation for Canada to celebrate its winsâand has affected Canadian entrepreneursâ tendencies to see themselves playing a bigger role on the world stage.

âAmericans are so good at telling the entrepreneurial story and Canadians need to improve. In the mythology of Silicon Valley, we are surrounded by the Elon Musks, the Steve Jobses. Who are those people in Canada? Most kids in high school donât even know who Tobi LĂŒtke is,â says Anthony Lee, a managing director at Altos Ventures and co-founder of C100, referring to the founder of Canadian e-commerce behemoth, Shopify.

People here like to say that the longer you live outside Canada, the more fiercely Canadian you become. The charter members of C100âa Whoâs Who of Canadian technoratiâpay for the privilege of participating in events and volunteering their time, not the other way around. Leckie defines the job as âmaking sure that people know Canada is kicking ass.â

He meets me at his officeâa bright, wood-beamed space whose windows overlook San Franciscoâs Pier 33, where tourists queue up along the ferry dock to Alcatraz. In a previous life, before attending Stanford University, Leckie was a member of the Canadian Sailing Team, who represented his home country at the Pan American Games. But the plaque he keeps in his office has nothing to do with sailing competitions. He excuses himself and comes back a minute later to show it to me: a hockey puck mounted on a trophy base, presented to Leckie by C100 to thank him for his work as an inaugural co-chair of the organization.

Yet judging by how Canadians back home perceive the diaspora, people like Leckieânot to mention Lee and his C100 co-founder Chris Albinsonâcould represent the face of the âbrain drainâ as much as any of the young engineering grads migrating down from the University of Waterloo or the University of Toronto today. They had intended to come to the Bay Area for a year or two before returning home, but ended up staying. They are giving their time (and, sometimes, money) to help Canadian companies succeed. But they are agnostic on the question of where Canadians should locate their startups, at least in the beginning stages.

âWe think people ought to be in the ecosystem here, to be a part of it. If you want to be a giant in tech, you have to spend some time down here. But you donât have to stay here,â says Lee.

Albinson cringes at âbrain drain.â âItâs a term I find horrifically bad for the country,â he says. âNo, weâve always been about supporting Canadian entrepreneurs. But if youâre only doing Canadian entrepreneurship in Canada, that gets away from this idea of flow. There should be no barrier for capital, people or information.â

Some of the people I interviewed for this story live in the Bay Area, while some have returned home to Canada. But none of them say their career trajectories would have been possible had they stayed in Canada, rather than coming to the U.S. for work experience. Thatâs changing now, but there is too much precedent to think it will end any time soon.

The early 1990s saw a wave of Canadians pouring into the Valley on the crest of the telecom boom. Two cohorts preceded them, but their names and stories are not widely known. This is where the details get sketchy, owing to a lack of published materials. Itâs hard to piece together a narrative from the paucity of recorded histories: unlike the volumes of work on Americans (including American immigrants) and their successive technologies, the body of information on Canadian tech achievers is, for the most part, paper-thin.

Iâm not the only one whoâs noticed, either. âIâve not come across an historian of Canadian technology. If you find said person, please share their name with me,â John Stackhouse tells me. The former editor-in-chief of The Globe and Mail now works for RBC, and is writing a book on the Canadian diaspora. He helped a bit with the following history.

Canadians at U.S. engineering schools in the â40s and â50s undertook advanced studies and research as part of the Cold War nuclear academic arms race. Starting in the â60s, Canadians are thought to have worked at companies like Fairchild Semiconductor, one of the early chipmakers that helped Silicon Valley get its name.

In subsequent years, Canadians were among the engineers who developed software programs, modems and routers at companies on both sides of the border. The University of Waterlooâs computer science program was established in 1964, soon becoming one of the biggest of its kind in the world, catching the eye of companies like IBM. Around that time, U.S. companies started hiring Waterloo grads, a tradition that continues today.

Some important names come up in conversations that track the origin story of Canadians in the Valleyâpeople of Canadian descent whom some of todayâs tech cohort have claimed as their forebears. Cecil Green, co-founder of Texas Instruments, was born in England and raised in Vancouver, where he studied at the University of British Columbia in the â20s. His financial gift helped build the universityâs Green College and a visiting professorship program. Gururaj âDeshâ Deshpande is an Indian immigrant who studied at the University of New Brunswick (UNB) and Queenâs University in the late â70s. He worked at a Motorola subsidiary in Toronto and later co-founded Sycamore Networks, one of the biggest IPOs of the telecoms era, and endowed an innovation centre at UNB. And then thereâs James Gosling, the father of the Java computing language, who was born and raised in Calgary and worked at Sun Microsystems for nearly three decades before moving on to Oracle, Google and Amazon Web Services.

By the â90s, Canadians were thick on the ground in early computer software, graphic design, telecoms and mobile. And then they started climbing the masts of the Silicon Valley flagships: Shaan Pruden at Apple, Jeff Skoll at eBay, Don Listwin and Rob Lloyd at Cisco, Jeff Mallett at Yahoo, Doug Roseborough at Oracle and Rob Burgess at Macromedia (now Adobe). The list really does go onâand thatâs before you get to todayâs top Canadians who occupy the upper ranks at marquee companies like Facebook, Dropbox, Uber, Google, Salesforce, Zynga and Slack.

Silicon Valley Canadians of the late â90s and early aughts didnât have a lot of ways to find each other. There wasâand still isâthe delightfully-named Digital Moose Lounge, which hosts social gatherings like Canada Day events. Aside from that, people were mostly dispersed, ending up camouflaged among American colleagues at work. Later, when LinkedIn came along, Leckie created a âCanadians in the Bay Areaâ LinkedIn group, and Canadians started self-identifying. That helped form the basis for C100âs early outreach.

The Canadian ability to blend in has made it surprisingly difficult to pin a number on the population of expats in the Bay Area; various estimates peg it at somewhere between 250,000 and 350,000. Not even Rana Sarkar, consul general of Canada in San Francisco and Silicon Valley, knows for sure. He says, âA good chunk may have dual passports andâŠare inadvertent Canadians: either their parents are Canadian, or they moved down here at a young age or theyâre laying low and have married an American.â

But the central question of what constitutes a Canadian is an interesting one, he reckons. What about people like Deshpande and Musk, who passed through Canada and occasionally reference their maple-leaf roots? âIf someoneâs mom or dad is a Canadian and theyâve only visited the country a few times, does that mean theyâre a Canadian of interest?â Sarkar asks. If the answer is yes, the narrative of the Canadian diaspora will need to be expandedâand many in the Valley think Canada will the better for it.

â

Thereâs an expression Albinson, the C100 co-founder, uses often: âWhen the United States catches a cold, Canada catches the flu.â In 2008, Canadaâs tech sector had a bad flu in the midst of the financial crisis. âCanada, as an innovation economy, was on deathâs door,â he recalls. âThere was no venture capital. There was no angel money. And all over the country, entrepreneurs were losing their companies. Nortel was dead, Research in Motion [known as BlackBerry] was wobbly.â

It took a crisis for Canadians of the Valley to see themselves as a collective asset.

In addition to co-founding C100, Albinson is co-founder of Founders Circle and Panorama Capital. A Kingston boy, he was always intrigued by a painting of the Golden Gate Bridge that his grandmother brought home from a trip to San Francisco. He dislikes hierarchy and the East Coast. And he loves the weather and beauty of his adopted home of Larkspur, a little town in Marin County, Calif., where he meets me in the garden patio of a restaurant with fountains and birdsong.

Back in 2002, when he was a venture capitalist at JP Morgan Partners, Albinson was part of a trip to India designed to showcase the countryâs goal of becoming a technology leader by 2020. In Delhi, he witnessed the benefits of viewing Indian expatriates not as a lost liability but rather as an asset. The Indus Entrepreneurs (TiE) is a Silicon Valley-based non-profit that connects entrepreneurs with South Asian roots around the world with funding, networking, education and mentorship. Founded in 1992, TiE became a model for C100 to emulate in building its own support ecosystem for expats.

By contrast, in 2008, Canada had few startup incubators. And it had a tax law requirement that made foreign venture funding of Canadian startups so difficult that investors were skipping the country altogetherâCrunchbase called it âa leper colony for tech entrepreneurs.â Canada eliminated the tax section in 2010, after lobbying by stakeholders like C100, says Albinson.

âWe realized the Canadian environment was very fractured,â says Albinson. âOne of the reasons why Canada wasnât having that much success wasnât that the entrepreneurs werenât good, but because the ecosystem around them was a mess.â

Albinson and Lee hatched C100 together just minutes after first meeting at an event in Palo Alto sponsored by the Canadian government. The consul general wanted to recruit them to a business advisory board to stimulate industry connections, but they had a better idea.

In January 2009, Albinson stood in front of the 85 most successful Canadians in a conference room on Sand Hill Road, the so-called âWall Street of the Westâ in Menlo Park, Calif.. He cleared his throat and issued a call to action on behalf of their homeland. âI looked them in the eye and said, âYouâve had the privilege of a passport, youâve had an amazing education. Because youâre in this room, youâve had a lot of success down here. You have a responsibility. We want to start this. You owe it to these entrepreneurs to do this.ââ

Lee says they felt inspired by Own the Podium, the national campaign (now a non-profit) to invest in Canadian winter sports that helped make Canada the top gold-medal finisher at the 2010 Vancouver Olympics. âIt was very un-Canadian to say, âWeâre going to win,ââ says Lee, âand I think it was kind of a turning point for the Canadian psycheâ (Later, C100 created its own video homage to Own the Podium with a Silicon Valley twist: âItâs about claiming the podium as ours, painting it red and white, crushing it and sprinkling the dust into the eyes of our competitorsâ).

Albinson and Lee werenât sure if their pitch would work. It was a novel ask, and people inside the room had no reason to contribute, other than their patriotism. âWhat I didnât know was, did the thing that burns inside me about being Canadian, was that in everybody?â says Albinson.

Nearly everyone took out a pen and wrote a cheque for US$850.

â

What a difference a decade makes. As Canadaâs tech sector gains traction, government support and major venture capital from south of the border, the freshly-laid infrastructure convinces top Canadians in the Valley that the growth trend will accelerate. Itâs when someone like Montreal native Patrick Pichette moves on from his role as CFO at Google and turns venture capitalist, joining iNovia with the express purpose of elevating Canadaâs best startups. Or when homegrown Hootsuite hero Ryan Holmes uses his success to build a national entrepreneurship accelerator to help youth in Canada launch the next big thing.

In 2017, Canadian companies comprised 14 per cent of the Deloitte Technology Fast 500, which tracks the fastest-growing tech companies in North America, up roughly three per cent from the year before.

Today, itâs U.S. venture firms that are working to get in front of Canadian entrepreneurs. Andrew DâSouza, co-founder and CEO of fintech service company Clearbanc, says he personally hears from at least one U.S. venture capitalist a week, usually from San Francisco or New York, asking him for advice on whom they ought to be meeting with in Toronto. âPeople are starting to wake up and realize thereâs great talent and great companies built here,â he says.

Itâs no longer strictly a requirement for Canadian entrepreneurs to knock on Silicon Valley doors for Series A funding, or even to base their companies in the Bay Area, says DâSouza. But you do need a âgood connectionâ in the Valley, if only to level-set with the competition. âIn Canada itâs very easy to be a big deal before youâve accomplished very much. You can get in The Globe and Mail and you can get on TVâŠ. Itâs helpful to be able to look up and realize youâre actually competing on a global scale.â He co-founded Clearbanc in San Francisco in 2015, but a year later, it was clear the conditions were right for a move to Toronto. Now he recruits from both countries.

Albinson talks about being Canadian as though it were a superpower. âYou tell people, âIâm Canadian,â and suddenly youâre into three levels of trust. You need to be very, very careful with that. Thatâs one of the things I tell the C100 folks: we have this amplification that weâve been entrusted with, whether we know it or not.â

More than a decade after Canadaâs telecoms era sputtered, the countryâs tech economy has all the ingredients it needs to dominate. Whatâs missing right now may not be something C100 can provide.

âItâs almost just a matter of confidence,â says Lee. âOne thing Iâve noticed is that Canadians working in any industry will pay more attention to Canadians outside the country. Canadians have always needed outside validation. Itâs always been part of the culture.â

He pauses. âPart of what weâre trying to say is, âStop it, already.ââ

Americans donât need to name their success stories constantly because theyâre all sewn into the mythology. Theyâve managed to make all their disparate stories into American onesâto give them an inevitability. But in this case, history is being made in real time by Canadians at home and abroad in an industry that has little narrative of its own.

Canadians will recall getting intermittent history lessons on TV in the â90s by way of âHeritage Minutesââ those iconic national video clips depicting important Canadian moments. Theyâre how we learned about Canadaâs contributions to basketball, Superman and even the real-life bear that was said to have inspired Winnie the Pooh. But why not the father of Java?

âI grew up during the Canadian iconography era,â says Leckie, referring to those film clips. âItâs always been my goal that Canadian tech would have that moment in the sun.â

If that happens, it will need to include the Silicon Valley diaspora.

Tags: brain drain, C100, Canada, Julia Scott, Silicon Valley, The Logic

Posted in Uncategorized | No Comments »

Beyond #MeToo: Teaching Boys About Consent

Wednesday, January 24th, 2018

Coaching Boys Into Men

When is the right time to start teaching young boys about consent, boundaries and respect toward women?

A nationwide program called Coaching Boys Into Men trains school coaches to work with boys as young as 11, who are on their school’s athletic teams. Boys trust their coaches, and the conversations that ensue are designed to plant seeds that will help prevent abuse — and give young men the tools to speak up when they see something that’s not right.

Student athletes are often the leaders at their schools, and they can set the tone for the other students.